"The highest possible standard of gallantry and determination"

Born Fremantle on 1 August 1914. 39005 RAF, 139 Squadron RAF

Commanded 105 Squadron RAF 1942–43,

RAF Binbrook February, 1943 – October, 1944, RAF Station Chittagong 1945

Extracts/sections

Extracts from letters and book "Per Adua and all Dat Jazz" supplied by Wing Commander Les Sullivan. Written by the late RAF Wing Commander Laurie Osborn, MBE, DFC.

No. 13 Operational Training Unit, Bicester.

Without the benefit of any formal training in the conduct of life in the Officer`s Mess, the problems one faced in those early days are best glossed over, particularly in so much as a Commissioned Observer was a rare species at that time. I was, perhaps, fortunate that at this particular time most were already Flight Lieutenants, with the occasional Squadron Leader who has survived the initial phase. Names like Peter Simmonds, Bob Dore, 'Paddy Menaul', Langebeare, Searby, Cooper, Judson, Craig and if those weren't sufficient flipping though my logbook again, I see many names that I have long forgotten. Nobody thought for one moment that most of them would no longer be alive a year later.

To have already survived six months, even more in some cases, of low level attacks on German submarines and escorts gave these men the aura of living Gods and it was inconceivable that I should be rubbing shoulders and drinking beer with them.

But, the 'honeymoon' had to end and the time came for us to be 'crewed up'. This was arranged more or less by mutual consent between the pilots, observers, and wireless operator/ air gunners who were ready for posting to an operational squadron. For my part, I was content to throw in my lot with a pint–sized Sergeant Pilot called Dougie Weir and a ginger–haired Sergeant W/Op Air Gunner by the name of Bob Raisbeck, but known to all of course as 'Ginger'. Dougie was a first class soccer player, he seemed natural to keep me with an air of confidence and good humour that rubbed off on all who came into contact with him, but sadly, his flying skills did not match up with his confidence.

We were soon poached by a very senior Flight Lieutenant who had been doing a refresher course at Bicester before joining a squadron. A tall, taciturn Australian with a very severe limp, Hughie Idwal Edwards soon made it clear that he was not only the captain of the crew, but that if we wished to remain as his crew, we would have to meet the high standards he set.

Our only conflict concerned the merits of the quarter–inch scale topographical map as opposed to those of the 'half million' (1/500000) scale. Since I preferred to map read using the half million scale map and Hughie insisted I use the quarter inch scale, we compromised and I modified my Bigsworth Plotting Board to take both – not an easy feat when you are trying to fit a six foot frame into a four foot snout of a Blenheim, often with F24 camera, a three foot square plotting board and sometimes a tommy gun to keep you company. It became a case of squeezing in before take off, squeezing out after landing and in between, keeping your trust in the Lord and your bowels under control. Taking off in the nose compartment of a MkIV Blenheim was definitely not the most pleasant aspect of a navigator's life. Thank God for hydraulic undercarriages at last – no more winding the undercarriage up and down!

Sometimes it all got a bit too much, such as the occasion when we were sent out to produce a cine film for a simulated navigation exercise. In trying to keep up with Hughie's terse instructions whilst crammed into the cockpit beside him, with a 20lb F24 camera dangling from a pair of over–worked hands out of the side–window, it was a choice of either chopping off my hands on the rim of the window or letting–go of the camera. I chose the latter, with alarming results. Some holidaymakers crossing the Market Square below were startled to have an enormous camera descend amongst them and fly to pieces. Fortunately, no one was hurt and they saw the funny side of this 'new' method of taking aerial photography, and we got away with it!

We seemed to perform well as a crew and by the beginning of September we were starting to think about a posting to a squadron and rumours were rife as to our destination. During the first three weeks of September, we'd heard of posting to just about every 2 Group station in East Anglia and by the time our final night cross country exercise came around, all we wanted was to get the thing over with and get the hell away from Bicester.

24th September 1940 duly dawned and we were dispatched over to Kidlington, Oxon in the afternoon to carry out a couple of circuits and landings before setting off on a three hour night cross country, with a further couple of night landings at Kidlington before returning to Bicester. What followed was a catalogue of mishaps starting with the extinguishing of the flare path as we made our approach at the end of a virtually perfect cross country exercise. After several abortive efforts to make radio contact with Air Traffic Control, and a couple of extremely hairy approaches, we abandoned all hopes of landing in the darkness, and orbited the Oxford area in the vain hope that we would sooner or later make contract with Air Traffic; or that the flare path would be relit.

I tried to convince my pilot that our best course of action would be to head for East Anglia where there were some half dozen airfields which we should be able to make contact with on the 2 Group frequency. He chose instead to continue to orbit the Oxford area until it became clear that we were, to put it mildly, 'lost'. We had now been airborne almost six hours, during which time we had made two abortive attempts to land on a pitch–black airfield at Kidlington; two approaches to a railway station, which later turned out to be Reading, played ducks and drakes with our anti–aircraft batteries south of London, who had lost patience with an aircraft not only sounded and looked like a Heinkel, but persisted in firing off the wrong colours of the day; brushed with a Dornier which was no doubt the real target of the anti–aircraft batteries; clobbered a barrage balloon cable in the Southampton area, and all in all, had done our utmost to turn a routine cross country exercise into a major catastrophe.

By now it was clear we were in a serious situation, so the skipper decided to climb to a height where we would at least be safe from any further trouble with barrage balloons. He levelled out at 10,000 feet, but it was soon evident that it would be too cold for us to stay at this height for very long, the heating system was not adequate to cope with the sort of cold we were experiencing. Bob was already complaining about the cold, so Hughie ordered him to leave his position in the turret and come up to the cockpit where he took the right hand seat I had occupied, whilst I moved forward into the nose compartment which housed my small navigation table and the bombsight. To help Bob recover I passed my fur lined Irwin flying jacket to him as I was also wearing a sturdy pair of flying overalls. As I crouched in the nose on my tiny seat at the table I connected the Aldis lamp to the aircraft power supply. The Aldis lamp was a very powerful hand operated signalling lamp and had a red and green filter which could be attached for other signals purposes, such as acknowledging take off or landing instructions transmitted from Ground Control.

From the occasional sighting of towns and other landmarks by the light of the moon, I was still confident that we were somewhere north of Southampton and a sudden flurry of anti–aircraft and searchlight activity a few miles to the south convinced us that bombing raids were in progress along the south coast at Southampton and Portsmouth. As the cloud broke and the moon shone through, we became increasingly certain that we were somewhere over the South Downs area, and the sudden, if fleeting, glimpse of a flashing occult beacon on our port side confirmed from its identification code that it was indeed one of the navigational aid beacons that prevailed across the country. From the navigational aids information material we always carried, I pinpointed it as being at Andover, one of a half dozen grass airfields in that vicinity.

When I gave the information to the pilot, he immediately gave us the option of baling out or risking a blind landing, using the flashing beacon as the landing point. Both Bob and I decided we would bale out, a decision which Hughie heartily endorsed. From my cramped position, I endeavoured to release the escape hatch which was situated in the floor of the nose compartment, but try as I might, I could not move the lever that secured the hatch enough to operate the release mechanism. The only alternative was to force the lever, using the small axe which was also housed in the nose, but in my efforts to tear it from its housing, I broke the holding straps and the axe remained secured fast. I reported the problem to the skipper and suggested we bale out through the top hatch, above his seat. This he refused to order and we learned that it was precisely due to such an escape that he had lost part of his foot a year earlier when baling out of a short nose MkI Blenheim which did not have the nose compartment with escape hatch. By this time we had reduced our height to about 5,000 feet, where we were much less cold and from where, when all the clouds broke, we were able to see the flashing beacon and the darker contours of the land below a bit more clearly.

The skipper made his decision to land and gave me instructions to make good use of the Aldis lamp and to warn him the instant I saw any sign of obstacles below or ahead of us. In retrospect, it was a pretty futile order. At 2,000 feet, it was clear that the south coast ports were indeed being heavily raided and as we passed into the area we were ourselves subjected to the occasional burst of ack–ack fire and the fleeting attention of a searchlight. We were committed to a blind landing and slowly descended through the patchy cloud in a wide orbit, trying always to keep our beacon in sight. We had no way of knowing what the barometric pressure was, so the pilot retained the same barometric reading on the altimeter that we had been given for our landing back at Kidlington some hours earlier. We would have to take a chance that here had been no significant change since then. Every one millibar change in pressure meant some 15 feet change in height, so it was important that our altimeter should register the correct height above ground.

At 1,000 feet, the pilot told us he was going to make his landing attempt at the end of the next circuit. He switched on the aircraft landing light and commenced the landing pattern. He carried out the normal drill for a standard landing by lowering the undercarriage and selecting 15 degrees of wing flaps to allow us to fly much more slowly in our approach to the beacon without stalling. He reduced airspeed to 120 knots. I turned my Aldis lamp towards the ground below, just as the skipper shouted for us the brace ourselves. Suddenly, I saw below us the tops of trees flashing by and I immediately swivelled on my seat to warn him. His reaction was almost simultaneous as he too saw the trees in the light of the landing lamp. As he pulled the nose of the aircraft up, there was a sharp sound of tortured metal as the aircraft, now down to less than 100 miles an hour, crashed through the uppermost braches as it plunged towards the ground. The pilot must have cut the engines at the same time as he had seen the treetops, an action which undoubtedly saved our lives by preventing us plunging directly into the ground. My final recollection before losing consciousness was one of receiving a heavy blow across my back and a sensation of being hurled through a heavy window. There was a frightening sound of metal being torn, before I found myself being bounced along the ground, having obviously been projected through the nose of the aircraft and into the trees. Then all the lights went out and there was nothing.

We had been airborne for over six hours and therefore so low on fuel that there was no explosion and no fire. Nevertheless, the impact was sufficient to cause the aircraft to disintegrate and our survival was nothing short of miraculous. There is no doubt that the skill of the pilot in nursing the aircraft to the beacon and making such a flat approach, allowed the trees to cushion our impact. When I regained consciousness, it was still very dark with the moon shining through the trees. I was suffering excruciating pain in my back and what seemed to be complete paralysis of both legs. They felt as if they were immersed in concrete. Bob Raisbeck was laying across me and there was no sign of the pilot. I tried to renew my efforts to get up, but to no avail.

I became aware of voices in the distance and could see faint lights flickering through the trees. As they came closer, I managed to raise some sort of cry for help. Within minutes, the first of them had found the wreckage and I was soon bathed in the beam of a torch and seconds later, we were surrounded by a half a dozen or more men who seemed convinced that they had captured a couple of German bomber crew. Their questions came fast and furious, until one of them saw that Bob was obviously seriously injured and that I was soaking with blood and unable to move. They still weren't too keen to give us help, until I was able to convince them that we were English and that the aircraft in the woods was a Blenheim. At that point, Bob regained consciousness and the scene took on the look of a farce, principally because Bob spoke with a rich Geordie accent which they could not understand. Fortunately, one of the men a member of the Home Guard took control. Within minutes, he had sent somebody to find a telephone and alert the authorities and call for an ambulance.

At this stage, both Bob and I had passed out again and when I came to, we had been covered with the silk from one of the parachutes and I was in considerable pain and difficulty. The Home Guard explained that because of the heavy raids on the south coast ports, there were no ambulances available, but as good luck would have it, a veterinary surgeon from the local town of Lichfield was on duty with the Animal Hospital Ambulance and was on his way to help. After being pumped full of morphine, this skilled veterinary surgeon then drove us across open fields in a three ton truck which had been converted into an animal ambulance. At six in the morning, some eight hours after we had taken off on an innocuous night cross country exercise, we arrived at Park Prewett Hospital on the outskirts of Basingstoke. Our skipper had been found wandering on a road on the other side of the wood, looking for his crew. He had also been taken to Park Prewett where he was found to be suffering from concussion and a badly cut top lip!

Three months later, whilst Bob and I were still languishing in hospital, Hughie Edwards led a formation of six Blenheims on a daring raid on the Power Station at Bremen in broad daylight, a mission for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross and which was the start of a remarkable war career that was unsurpassed by any other airman.

From a letter after reading obituaries published in Australian newspapers of his "old skipper" Sir Hughie's death in 1982:

"Hughie was a man and only one of two RAF officers for whom I had not only the greatest admiration but also respect. So I was slightly incensed by the remininiscences of the two reporters both of whom seemed to portray him as a sort of eccentric cavalier who daredevilled his way through the war from escapade to escapade. My personal memories of Hughie are somewhat different and I am sure that Australians fail to realise that he was in fact a far, far greater man than generally portrayed; VC and all. The reporter spoke of the bomb aimer being in front of Hughie when he landed. I always had to sit in the long nosed snout of the Blenheim because he needed someone there to reassure him. Whilst we were very close before our crash in September he confessed to a slight fear of landing – my belief is that he drove himself to fly – that's real bravery!"

From a letter in 2000 on reading of the dedication of the Hughie Edwards Memorial Rest Area near Canberra.

"I was very interested in the Hughie Edwards article despite the beggar bogging off to get a VC without me. To think that if we had not pranged (in 1940) on our final night cross country I'd have been a hero -- or dead! In the six months or so that I was his navigator I found him to be a bit of an enigma and the prognostications in all of his biographies I find very interesting and amusing. In those days he was first and foremost just another bloke in Air Force blue instead of the later darker blue with a couple of rings although a Flight Lieutenant was pretty big time then and warranted an occasional "Sir" if we adjudged him to be in the right mood so I called him "Sir".

Humour was not his strong point and I don't think he would have appreciated those comments about his "luck" etc. Actually we got to know each other quite well and I think he even liked me but he was a very private person whose only aim was to kill Germans. For me he wasn't the best pilot in the world and I wasn't keen on his insistence on having me in the snout of the Blenheim which was not the best place to be as was evidenced the night we tried a blind landing with very unpleasant consequences but which set in train a pattern for the rest of the war and thereby saved my life!"

As Wing Commander from May 1941 – September, 1941, where in June 1941 he won his first decoration, the DFC, for the part he played in a low level attack on armed ships off the Dutch coast, and three weeks later on July, 4th, he planned and led his squadron of Blenheim bombers in a daylight low level attack on Bremen for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross. Bremen was one of the most heavily defended targets in Germany and to attack it in broad daylight flying Blenheims, which were a vulnerable aircraft at the best of times was a most hazardous operation. His V.C., citation was as follows;

"Wing Commander Hughie Idwal Edwards DFC, although handicapped by physical disability resulting from a flying accident, has repeatedly displayed gallantry of the highest order in pressing home bombing attacks from very low heights against strongly defended objectives. On 4 July 1941he led an important attack on the port of Bremen one of the most heavily defended towns in Germany. This attack had to be made in daylight and there were no clouds for concealment. During the approach to the German coast, several ships were sighted and Wing Commander Edwards knew that his aircraft would be reported and that the defences would be in a state of readiness. Undaunted by this misfortune, he brought his formation fifty miles overland to the target, flying at a height of little more than fifty feet, passing under high tension cables, carrying away telegraph wires and finally passing through a formidable balloon barrage. On reaching Bremen he was met by a blast of fire, all of his aircraft being hit and four of them being destroyed. Nevertheless, he made a most successful attack, and then with the greatest skill and coolness withdrew the remaining aircraft without further loss.

Throughout the execution of this operation, which he planned personally with the full knowledge of the risks entailed, Wing Commander Edwards displayed the highest possible standard of gallantry and determination".

Wing Commander Edwards was selected to accompany a group of distinguished RAF commanders under the leadership of Air Vice Marshall Arthur Harris on a goodwill mission to the United States, as a specialist in bombing. The mission left on the 18 October,1941, and traveled extensively on inspections and meetings when on their final visit to the Boeing factory in Seattle, before leaving for Canada, they were told that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbour. In Canada he visited as many training stations as possible before the mission's return to England in time for Christmas 1941.

By the first flight of the Mosquito prototype (W4064) in 1940, the Royal Air Force knew it had a winner – a little wooden twin–Merlin–powered bomber with the performance of a fighter. The majority of the first order for the Mosquito was changed from bombers to night fighters. Soon after the introduction of the Mosquito NF II, these aircraft were used on intruder missions over occupied Europe. The idea of a dedicated fighter–bomber led to the creation of the Mosquito FB Mk VI, the most–produced version of this aircraft. The FB VI, with the 'universal wing,' first entered operations in the summer of 1943.

The Mosquito first found fame with the series of low–level daylight raids led by Wing Commander Hughie Edwards with 105 and 139 Squadrons, the first units to take the Mosquito B Mk IV into combat. Their raids against Gestapo headquarters became the stuff of legend. Indeed, what could be more dramatic than flyers hurtling at rooftop height across Europe, their only defense being their high speed and the penalty of a moment's inattention was becoming a fireball in the European countryside? Their objective was saving men and women brave enough to confront the Nazi evil to free their countries.

Just prior to the introduction of the FB VI in 1943, 105 and 139 Squadrons were absorbed into Bomber Command's pathfinder force, 2 Group. This group became the basis of Second Tactical Air Force (2TAF) in July of 1943, with the objective of supporting the invasion of Northwestern Europe.

He was then appointed as Chief Instructor for No 22 Operational Training Unit, much against his wishes. He was then appointed as Commander of 105 squadron, in August 1942. 105 squadron had recently converted to Mosquitoes and Wing Commander Edwards made a big impact on the method of operation, and attack when flying the mosquitoes, and further distinguished himself becoming quite a legend in 105 squadron, where he was awarded a D.S.O., for his leading an attack on the important Phillips Stryp Group main works and the Emmansingel valve and lamp factory at Eindhoven in the Netherlands, only 50 miles from the Ruhr.

In May 1943 Group Captain H. I. Edwards, the first airman to win the VC, DSO, DFC, was appointed station commander at Binbrook, home of 460 Squadron. Group Captain Edwards came to the squadron with a reputation already made by his earlier wartime exploits, and no one except himself knows exactly how many operations he undertook during the war. Although Binbrook records 11 operations, he was also credited with 15 operations and to Binbrook personnel this was seemingly an understated tally of operations.

His technical knowledge and his personal operational ability was altogether outstanding . His courage, both moral and physical, is exceptional, and as a technician he is unrivalled. He did not humour fools or accept reasons for less than utmost effort. It was his personal belief that any decoration should be thoroughly earned.

Group Captain Edwards came to the Binbrook with a reputation already made by his earlier wartime exploits. For instance, his first official mission with 460 did not take place until some time in 1944, but many a new crew on their first operation during the long, hectic and lonely nights of 1943, had Edwards at the controls of their bomber. No deed could ever inspire greater confidence in a "sprog" crew than such an act as this, and together with his stirring "you must press on regardless of opposition" to the crews at briefing, he set a truly magnificent example.

Whilst many other station and squadron commanders were showered with decorations, Group Captain Edwards did not receive any decoration for his flying, nor his commanding of Binbrook station nor his flying on 460 squadron, where it was thought he did at least another tour unofficially, enhancing the reputation of such a magnificent record breaking squadron. Group Captain Hughie Edwards had a remarkably outstanding war career that was unsurpassed by any other operational airman.

Hughie Edwards was a tall, slimly–built West Australian who transferred from the RAAF to the RAF in 1937, and it was only after his gaining a short–service commission in the RAF that he appeared to have found his niche in life.

His earlier life was undistinguished except for a period when he was an Australian Rules footballer with the famous South Fremantle team for whom he played on the half–back line, and the rugged qualities which are demanded of a player in that position seemed to set the pattern for his later exploits.

He won his first decoration, the DFC in June 1941, for the part he played in a low–level attack on armed ships off the Dutch coast, and three weeks later on July 4th, he planned and led his squadron of Blenheim bombers in a daylight attack on Bremen for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC).

Bremen was one of the most heavily defended targets in Germany and to attack it in broad daylight flying Blenheims, which were a vulnerable aircraft at the best of times, was a most hazardous occupation, and more so when on this particular day there was no cloud to give the raiders any cover. After crossing the German coast he led his squadron at a height of about 50 feet, flying under numerous high–tension cable, and approached the target by flying through the balloon barrage which encircled the city.

As they passed on over the grey slate roofs of Bremen through a wall of flak being fired at point–blank range, Edwards' Blenheim just missed hitting a concrete pylon, but could not avoid gathering up telephone wires and several other aircraft of his formation were also trailing snapped off lengths of wire. Below then the crews could see people taking cover behind motor cars as the bombs burst on timber yards, factories, buildings, a railway junction and the docks. The wreckage from the timber yards was thrown hundreds of feet higher than the raiders, and in the murderous criss–cross of flak every aircraft was hit and four were destroyed. As the conclusion to his citation reports, he then "with the greatest skill and coolness, withdrew the surviving aircraft without further loss."

His DSO came in January, 1943, when he led a daylight attack by Mosquitos on the Philips' radio valve factory at Eindhoven, an operation which was subsequently described as "faultlessly executed."

His successor, Keith Parsons was posted to command 460 squadron, as a Wing Commander, then replacing Hughie Edwards as Binbrook station commander, where although he was not supposed to be flying on operations, did so earning a DSO, adding to his DFC, AFC, and later a CBE, plus becoming a rare Air Commodore caterpillar wearer and one of the higher decorated Royal Australian Air Force pilots.

Such a man was Hughie Edwards, aged 29 years at this stage, the tales of whom are legendary regarding his fearlessness on operations, and who could have, had he desired, won many more richly deserved wartime honours. However, despite his innate modesty, he finished the war one of the most highly decorated airmen and the most highly–decorated Australian in World War II,

Group Captain Edwards, in an informal discussion with Group Captain W. D. David, CBE, DFC, AFC

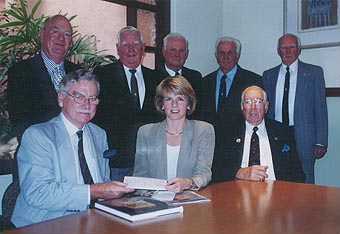

Julie Bishop presents a cheque to 460 RAAF Squadron Association. Back L-R: Graham Reynolds, Neville Johnson, Alan Forbes, John Currie, Clarrie Taylor. Front L-R: Peter Firkins, Julie Bishop, Jack Edwards.

Julie Bishop presents a cheque to 460 RAAF Squadron Association. Back L-R: Graham Reynolds, Neville Johnson, Alan Forbes, John Currie, Clarrie Taylor. Front L-R: Peter Firkins, Julie Bishop, Jack Edwards.It may have taken 60 years, but a fitting tribute to a Western Australian who was the most highly–decorated Australian in World War II, the late Sir Hughie Edwards, is about to become reality, thanks to the efforts of a group of the hero's former Air Force squadron members.

Led by former 460 Squadron rear gunner and retired Australian military historian, Flying Officer (Ret'd) Peter Firkins, the group has raised funds from private donors, with support from the WA Lotteries Commission, to sculpt and erect a bronze statue honouring the former Fremantle boy.

Mr. Firkins, chairman of the Sir Hughie Edwards VC Foundation, masterminded the fundraising and selection of local sculptor Andrew Kay to give Sir Hughie permanent recognition for his World War II achievements. Julie Bishop presented Mr. Firkins with a cheque for $4,000 from the Federal Government, Department of Veterans' Affairs. The grant is part of the Regional War Memorials Project of the Their Service – Our Heritage program.

'Despite being the most highly decorated Australian in World War II, his bravery and great contribution to helping maintain our freedoms have gone largely unrecognised in his home State of Western Australia, he was a Fremantle boy from a poor family who went on to incredible achievement and we believe he deserved proper recognition for his deeds, but more importantly as a fitting role model for our younger generation,' Mr. Firkins said.

Raised and educated in White Gum Valley and Fremantle as the son of a Welsh immigrant working class family, Sir Hughie's bravery, skill, gallantry and leadership led to him receiving the Victoria Cross, Distinguished Service Order and Distinguished Flying Cross Before he commanded Binbrook, the jome of 460 squadron.

Sir Hughie served as Governor of WA for a brief period in 1974 before ill health forced him to retire. He died in 1982.

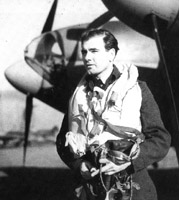

The sculpture, a life–size figure showing Sir Hughie in his pilot's uniform looking skyward and awaiting for the remainder of his squadron to arrive back from death–defying bombing raids over Europe, will be erected in Kings Square, near the Fremantle Town Hall.

Mr Kay said that his research revealed Edwards' tremendous consideration and care for those he served with throughout his career.

'He preferred to be involved in combat missions, in which he had a dogged determination to see it through no matter what the odds, over safer administration roles,' Mr. Kay said.

One of the ironies of Sir Hughie's achievements is that he was an average pilot.

Arthur Hoyle, in his book Sir Hughie Edwards, said: 'As a pilot Hughie was certainly below average, as was demonstrated by the quite large number of aircraft which he damaged or destroyed. He always had some difficulty landing, especially heavy bombers'.

Please also see the Group Captain Hughie Edwards plaque unveiling article as part of the 460 Squadron commemorative gathering in Canberra in 2003.