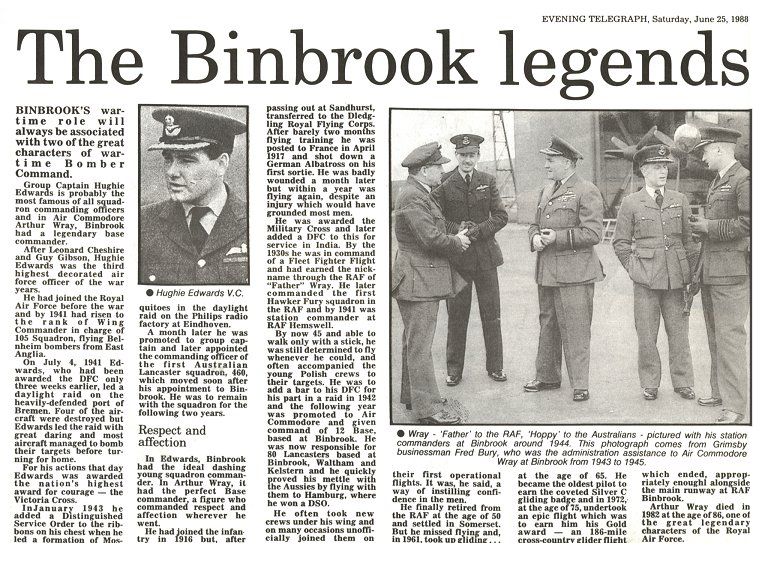

A Royal visit by King George VI and Princess Elizabeth on May 6th, 1943. The King talks with Air Commodore Wray while Wing Commander Chad Martin introduces a 460 squadron crew to Princess Elizabeth.

Binbrook becomes the home of 12 Squadron, 1945

In the group 4th from the left, the Duke of Gloucester visiting on July 20th 1944 watching the loading of the bombs in Lancaster D2 of "C" Flight prior to the raid on the railway marshalling yards at Courtrai in Belgium.

In the group 4th from the left, the Duke of Gloucester visiting on July 20th 1944 watching the loading of the bombs in Lancaster D2 of "C" Flight prior to the raid on the railway marshalling yards at Courtrai in Belgium.The Duke of Gloucester, the Governor General designate of Australia, was visiting the squadron on 20 July 1944, and after briefing and checking over our plane in dispersal, we had to stand by to meet His Royal Highness. It was all very exciting to be meeting up with royalty. Fancy him coming to see us. As time drifted on, we cursed HRH who was delayed in the officers' mess, and on shaking his hand in front of our K2 "Killer" we realised he had enjoyed some of the Australian hospitality served in the mess.

Extracts from Peter Firkin's "Strike and Return"

Wing Commander Chad Martin, DFC, became the first airman product of the Empire Air Training scheme of any nationality to command a heavy bomber squadron. He was appointed to 460 squadron with instructions to do as many operations as possible in the early stages. He had done his first tour in 1941, as a member of 57 squadron, RAF, and seldom did the citation to an award sum up a man's personality and character as Chad Martin's did when he was awarded the DFC. It read:

"On 24th July, 1941 this officer as Captain of an aircraft participated in a daylight attack on Gneisenau at Brest. Flight Lieutenant Martin kept in tight formation and with his leader, presented such a determined front that the numerous enemy fighters did not dare to attack. One night last Autumn, whilst flying to Berlin he failed to receive a general recall signal and went on to his target. He penetrated into the center of the city and bombed his target. On his return to this country, he made a successful landing in thick fog."

The last raid of his first tour were the three 1,000 bomber raids in May & June, 1942. Martin completed his conversion to Lancasters did a number of cross country familiarization flights and operated to Nurenburg within nine days of taking command of the squadron.

Shortly after Wing Commander Martin's arrival at 460 squadron at Breighton, two police constables called on him to devise some way of overcoming the removal of pushbikes from outside the Black Swan (Dirty Duck) and the seven sisters (The Fourteen Tities) at closing time, only to find their journey had been in vain, as when they were ready to leave both their bikes had vanished!!

The other story concerned six or seven of the (see wild colonials) boys riding their bikes back to Breighton after a night out in Goole, and a steam roller they came across parked on the side of the road. They decided it would be a fitting ornament for the mess, so a couple climbed aboard, threw some coal into the fire box, and, after some pushing and pulling of levers, the monster began to move.

As there was no mutual agreement on who would drive, whenever one pulled a lever the other automatically pushed one, consequently a rather erratic course along the road was set. However, a small crowd of bystanders had by this time gathered to watch the spectacle and, with plenty of encouragement being given, they pursued a course for Base, traveling at a speed which is not normally expected or required of a steam roller. However, about a mile short of their destination they took a dive to port, off the road, over a ditch.

The squadron shortly after moved to Binbrook where as June 1943, finished with a heavy attack on Cologne.

The squadron's 26 Lancasters stood at the dispersals on the 8th July, 1943, bombed up and ready to go when at 6 p.m. the alarm sounded and through an electrical short circuit the entire bomb load of one Lancaster was released and fell to the ground, causing the incendiaries to burn.

Two of the ground staff were inside the bomber at the time and they leapt out and tried to roll the 4,000lb (cookie) bomb away, but found it was hopeless and ran for safety. The bombs exploded knocking the two escaping airmen to the ground. The Lancaster standing in the next dispersal point burst into flames and about two minutes later its bomb load exploded throwing more incendiaries among the aircraft and setting fire to starter trollies and other equipment nearby.

With several airmen, Wing Commander Martin manned the fire tender and extinguished as many of the incendiaries as possible, until someone saw smoke pouring from another Lancaster. Martin together with Flight Sergeant A. E. Kan. the latter still shocked from the original explosion, climbed inside the smoking bomber and fought the flames with hand extinguishers.

When the fire was partly under control another airman climbed in and disconnected the electrical leads to prevent more bombs from dropping to the ground. By this time the fire was intense enough to cause the magnesium contents of the fuselage to flare up, and almost suffocated, the three men had to leap out.

Wing Commander Martin then climbed on top of the burning, fully laden bomber and stood there coolly directing operations until the flames were put out.

In half an hour the danger was past, and the ground crews began getting as many aircraft as possible ready for the night's operations. In spite of damaged runways and shrapnel torn bombers, 17 aircraft took of and bombed Cologne.

Group Captain Edwards, who had also been close to the scene of the mishap, swore that whilst going from one bomber to another in his staff car, he was doing about 50 and was passed by an RAF erk running from the danger area!!

With such courage being shown by the leaders it is no wonder that 460 squadron flyers set such outstanding records of service and of courage.

Most of you would be aware that following the end of hostilities in Europe, the Sqadron moved on the East Kirkby for "Tiger Force" training. Perhaps what we did not know was that 12 Squadron moved to Binbrook in September 1945 (from RAF Station Wickenby),

The Editor of the Wickenby Register Newsletter had the following to say about the transfer:

Binbrook - 1945

After saying appropriate good-byes to Wickenby we flew in formation to Binbrook on a beautiful September day - a shakedown trip for the new No. 12 Sqadron on its first post war peacetime stint, Nine Lancs, a new C/O. (Wing. Cdr. Stafford Pollein Coulson, DSO, DFC) and a new Flight Commander (Sqdn. Ldr. 'Paddy' Flynn).

The Station was deserted and empty except for an enormous amount of junk left behind by No. 460 Squadron - bikes by the dozen, old cars on every corner. Dustbins full of uniforms and silent radios on every shelf and window ledge. Needless to say, quite a lot of it was successfully salvaged. But there was something else.

Not exactly a ghostly feeling but certainly a noticeable tension, as if the operational tradition of the place, established with such valour and at such cost by the Australians, was tangibly at odds with we 'invaders'.

In due course we explored this grand and lordly place. Behind the Mess (and built ontso it with considerable skill) was the 'Village Inn'. The interior of this 'encroachment', as the Clerk of Works called it, was beautifully done out in brickwork and old oak timbers with oak furniture to suit. It had a magnificent oak bar opposite which was a fireplace fit to grade any Tudor mansion. Poignant to recall now, in pride of place in the corner of the bar stood a splended oak chair into the back of which was carved the name of Group Captain Hughie Edwards, V.C.

In the Control Tower the Aussies had left another legacy. The walls of the Flying Control room had been done out in a pale blue colour. The rear and side walls bore a frieze of roman lettering about eight inches high in gold - again expertly done.