c. 1945, The original grave of eight airmen of 460 Squadron RAAF killed on a raid on Chemnitz, Germany on 5 March 1945.

c. 1945, The original grave of eight airmen of 460 Squadron RAAF killed on a raid on Chemnitz, Germany on 5 March 1945. c. 1945, The original grave of eight airmen of 460 Squadron RAAF killed on a raid on Chemnitz, Germany on 5 March 1945.

c. 1945, The original grave of eight airmen of 460 Squadron RAAF killed on a raid on Chemnitz, Germany on 5 March 1945.This memorial is special to me as our navigator Donald George Hudspeth was a member of our crew until our fifteenth raid on Stettin where his arm was smashed and broken and he was grounded. When he was declared fit for flying again he flew to finish his tour with other crews.

Don Hudspeth should have been awarded a decoration for his effort on the Stettin raid

c. 1945. The original grave of eight airmen cf No. 460 Squadron RAAF killed ona raid in Chemnitz, Germany on 5 March 1945. The grave is marked by a large block of wood carved into an Iron Cross shape with the words 'Hier ruhen acht Englische Flieger + am 5 3 1945 Todlich Abgesturtz' -- Here lie eight English Airmen killed in a crash on 5/3/1945.

The pilot of the Lancaster aircraft was Flight Lieutenant (Flt Lt) John Cecil Holmes (pictured below) of Toowoomba, Qld. Flt Lt Holmes, a woolclasser in civilian life. He was promoted to Squadron Leader on 25 February 1945 and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for 'numerous operations against the enemy, in the course of which he invariably displayed the utmost fortitude, courage and devotion to duty'.

The members of the crew killed were:

Flt Lt John Cecil Holmes, pilot of 460 Squadron, RAAF

Flt Lt John Cecil Holmes, pilot of 460 Squadron, RAAF| Personnel no# | Rank | Name | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| 405792 | Flt Lt | John Cecil Holmes, DFC | RAAF, pilot |

| 412815 | Flt Lt | Thomas Ernest Victor Morgan, DFM | RAAF, air gunner and gunnery leader of the squadron |

| 409653 | Flying Officer (FO) | Ivan Sydney Baudinetta | RAAF, wireless operator, air gunner |

| 408440 | FO | Donald George Hudspeth | RAAF, navigator |

| 430159 | Flight Sergeant | T.T. Clarke | RAAF, second pilot flying with the crew on operational experience |

| 412167 | Warrant Officer | Alwyn (Elwyn?) Oswald Thomas Mayne | RAAF, air gunner |

| - | Sgt | J Young | RAF, flight engineer |

| - | Sgt | R. E. Hayward | RAF, bomb aimer |

Squadron Leader Carl Richard Kelaher & Crew

Visit to Denmark, 2003, by nephew, Victor R. Kelaher

Earlier this summer my wife, Pamela, and myself were invited to visit and stay with Mr and Mrs Ove and Lis Knudsgaard who live in the Danish city of Horsens on the east coast of Jutland. The invitation was extended to us so that we would have an opportunity to accompany them to a remembrance ceremony and pay homage to the memory of our cousin, Squadron Leader Carl Richard Kelaher, of 460 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force, on the 60th anniversary of his Lancaster bomber, EE138, being shot down in the early hours of 4th September 1943 killing him and the rest of the crew. These being:

The home base of 460 Squadron was RAF Station Binbrook in the County of Lincolnshire. At 7.58pm in the evening of the 3rd September 1943, EE138 took off from the runway at Binbrook, together with a number of other Lancaster bombers of the squadron for a raid on Berlin. A total of three hundred Lancasters took part in the raid and twenty–two failed to return to their aerodromes. In addition to EE138 being shot down, 460 Squadron lost two other planes and crews that night.

On the return flight to Binbrook Carl's aircraft flew across the centre of Jutland and just before reaching the North Sea the bomber was intercepted by a German night fighter over the village of Stadil in west Jutland. The fighter raked the Lancaster with cannon fire and must have caused serious damage to Carl's plane which, although continuing to fly out over the sea, banked around coming back low over Stadil again as though intending to make a crash landing. The pilot of the fighter attacked the aircraft again and according to eye–witnesses the Lancaster started to climb again into the sky but it burst into flames then plummeted down to the ground.

The area where it crashed was marshy bog land adjacent to a water filled dyke and upon hitting the ground the Lancaster disappeared below the surface of the land to become the coffin of Carl and the other seven members of the crew. At daybreak the German military attended the scene and recovered pieces of aircraft wreckage from the surrounding area. Whilst doing this they found a headless, limbless torso of one of the airmen and this, the Germans buried at the site.

The field where the Lancaster crashed belonged to a farmer named Ingemann Halkjaer, the father of Mrs Lis Knudsgaard. He arranged for the local carpenter to make a wooden cross, and once the Germans showed no further interest in the crash site, he laid this on the ground above the buried torso. At that time the Germans had forbidden the Danish people from showing any sympathy towards allied airmen who had been killed or shot down. The following year when reeds had grown up around the crash site Ingemann erected the cross over the grave. In 1947 the torso was exhumed by the War Graves Commission and reburied in Svinoe Cemetery, some fifty kilometres away, and marked with a headstone indicating it to be the grave of an 'unknown' airman.

In 1949 at the behest of Ingemann Halkjaer, the villagers of Stadil raised sufficient funds for a granite memorial stone, engraved with the names of all the crew, to be placed at the crash site with a small garden in front of it which today has flowers planted in it and is looked after by Lis's sister Karen. This memorial stone was officially unveiled on the 5th May 1950, the fifth anniversary of the liberation of Denmark, and present, representing King Frederick of Denmark, was Colonel Ole Olesen his aide–de–camp, and other dignitaries.

Three weeks ago at 7.30pm on September 4th, which was a bright sunny evening, Pam and myself, together with Catherine Walsh and her daughter, Amy, relatives of Warrant Officer Walsh, who had travelled over from Australia for the occasion, joined Ove and Lis along with forty–four local residents at the crash site in the farm–field to the west of Stadil on the 60th anniversary of Carl's Lancaster being shot down. We planted two heathers in the small garden of remembrance as did young Amy on behalf of the Walsh family, then Lis asked for a minutes silence which was followed by the Danes singing their wartime resistance song 'Altid frejdig naar du gaar' (Always cheerful when you go).

Everyone then adjourned to a nearby hall where Lis gave a talk about the events of that night in September 1943. On display in the hall were hung photographs of seven of the eight crew and one photo frame blank bearing only the name of Sergeant Rolfe. Lis lit a candle for each airman reading out details of each one in turn. The evening ended with the singing of the British and Danish National Anthems then everyone present linked arms for the singing of 'Auld Lang Syne'. As the meeting broke up one of the Danish gentlemen present came up to me, shook hands and said, "We Danes will never forget what the RAF and their allies did for us during those dark years of ccupation". It proved to be a very emotional evening.

Ingemann has since died but at the time he gave up farming and sold the land he arranged with the local municipal council to have the crash area declared a grave site and as a result the area around it is fenced off and a pathway maintained leading from the farm track so that the public can visit the site.

The present owner of the land is not allowed to disturb the area or the pathway.

The Air Force Memorial, Runnymede, lists the names of approximately 60,000 airmen, who lost their lives serving in Bomber Command in World War 2. Included are the names of 4050 Australians who made the supreme sacrifice and of those there are 1000 who have no known grave.

The following poem, engraved in a gallery window at the Runnymede Memorial, was written by a student, Paul H. Scott, soon after the memorial was completed in 1953:

The first rays of the dawning sun

Shall touch its pillars,

And as the day advances

And the light grows stronger,

You shall read the names

Engraved on the stone

Of those who sailed on the angry sky

And saw the harbour no more.

No gravestones in yew–dark churchyard

Shall mark their resting place;

Their bones lie in the forgotten corners

Of earth and sea.

But, that we may not lose their memory

With fading years, their monument stands here,

Here, where the trees troop down to Runnymede

Meadow of Magna Carta, field of freedom

Never saw you so fitting a memorial,

Proof that the principals established here

Are still dear to the hearts of men

Here now they stand, contrasted and alike,

The field of freedom's birth, and the memorial

To freedom's winning.

And as the evening comes,

And mists, like quiet ghosts, rise from the river beds,

And climb the hill to wander through the cloisters,

We shall not forget them. Above the mist

We shall see the memorial still, and over it

The crown and single star. And we shall pray

As the mists rise up and the air grows dark

That we may wear

As brave a heart as they.

– Paul H. Scott

Speaking on the 81st anniversary of the formation of the RAAF earlier this year, the Chief of Air Force, Air Marshall Angus Houston described the operational success and excellence that the Air Force had provided in four major wars and other emergencies, although, sadly, many had paid with their lives.

He said that a tragic example of this sacrifice were the losses suffered by Australian crews of Bomber Command, who comprised just two percent of the Australians enlisted in WWII, yet accounted for 20 percent of deaths in combat of all Aussies across the three services.

AEM Houston said that the Royal Australian Air Force's No 460 Squadron alone lost 1,018 crew. 'Against an establishment of about 200, this means the whole unit was wiped out five times over.". He stressed that the service, sacrifice and values demonstrated by these great Australians was an inspiration to the current generation of Air Force personnel.

It is dedicated to those men and women who served during the Second World War, both in the air and on the ground.

It was the inspiration of Mr Jim Davis, a former rear gunner on the Lancaster during the Second World War. He and the former commander of the Pathfinder forces, Air Vice-Marshal Don Bennett, fought for over nine years to have this monument erected on the Hoe and it is the only international air monument in the world.

The monument was unveiled by Air Marshal Sir John Curtiss, in the presence of the Lord Mayor of Plymouth, Mr Dennis Dicker, on Sunday September 3rd 1989, the Fiftieth Anniversary of the declaration of War.

Among the several hundred RAF veterans who paraded that day were representatives from seventeen countries, including the USA, the USSR, Poland, Czechoslovakia, the Netherlands, South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Granite has been used for the main body of the Monument, on top of which is the six-feet tall, bronze statue of the Unknown Airman, sculpted by Mrs Pamela Taylor.

Beneath this monument are the names of many Airforce Men and Women whose relatives wish their names to remain in perpetuity. Here also rest the ashes of Air Vice Mashal Don Bennett, CB, CBE, DSO. Commander of the Pathfinder Force No. 8 Group. Bomber Command. Requiescant in Peace.

An article from the newspaper "THE AUSTRALIAN", from Thursday April 6, 2000 by Jamie Walker, Europe Correspondant

The London sleet is falling in icy globs as Corporal Dhir Bahadur, of the First Royal Ghurka Rifles, blows into his bagpipes and fills the air with their mournful refrain.

Behind him a slice of Australia, a lump of Bondi sandstone hewn from that sun drenched coast, is lowered gently into place. The inscription reads:"In honour of the undying ANZAC spirit and the shores from which it came."

For Jill, Duchess of Hamilton, this moment has been a long time in the making. As a proud Australian who divides her time between the UK and Queensland, she was appalled when she realised, in the lead–up to the 50th anniversary of VE Day five years ago, that there was no dedicated memorial in London to the 5397 Australian aircrew who lost their lives over Europe and the Middle East during World War II.

She stomped about London to raise money for a monument in Battersea Park, which duly became home for a dawn Anzac service. Still what was Anzac Day without an Anzac memorial? She settled on the idea to bring a Bondi boulder to Britain. "Rocks and stones have an honoured place in all cultures," she says – there's Stonehenge, the Black Rock of Mecca, Australia's Uluru.

And Bondi, that iconic strip of sand formed by sandstone cliffs and brick and tile suburbia, is a shrine of sorts to contemporary Australian society.

"The same spirit which led young Australian men to spend weekends voluntarily rescuing swimmers from the surf, led them to enlist and brave the beaches of Gallipoli," she explained. Enter Miriam Cosic, a staff writer on THE AUSTRALIAN MAGAZINE. The Duchess had stayed in touch after Cosic interviewed her about her work as an author and conservationist and prevailed on Cosic to scout for a suitable boulder. The Duchess was adamant: it had to come from Bondi, never mind that the beachfront is covered by heritage protection Cosic got a break when she heard about an old cache of quarried sandstone which had been abandoned on a golf course. Perfect! The next challenge was to get the three quarters of a tonne rock to London. She approached News Limited, publisher of this newspaper, and the company agreed to cover it.

'To All Who Gave So Much,

Paid The Ultimate Price

So We Might Live In Peace,

We Thank You And Remember You'Binbrook Parish Council Epitaph – Nov 10th 1997.

by Dave Hatherell

It is really wonderful to have news of a small French town of Quiberon that has always revered the allied airmen who lay in its cemetery.

460 squadron RAAF members wish to express profound thanks to the residents of Quiberon, and to the other communities in France, in Holland, and other areas, who have honoured and kept the memories of our mates so dear. Thank you from the bottom of our hearts.

One Aussie –– Three Brits –– One Pole –– one unknown.

Sixty years later (2004) the local Museum planned an exhibition – as the wreckage is discovered.

Quiberon is a peninsula on the south Brittany coast down near St Nazaire and Nantes. Nowadays a very popular holiday resort where the population of five thousand swells to one hundred thousand in summer. The Germans took up occupation in June 1940, and the people had to make the best of it. The Bretons are a proud folk, with Gaelic traditions. Thus this was resistant, not collabo, country.

By and large the war past them by. In November 1941, the Kommandant of Nantes was assassinated, and 50 hostages shot. A few weeks later, 22 Squadron attacked Nantes on two consecutive nights. On the second raid, 02 December 1941, they took two losses.

One aircraft over the target and another, on its way back, exploded over Quiberon Bay, being witnessed by a young fisherman, who was dodging the curfew.

The crew were:

The next morning, three of the four crew of the Beaufort were washed up on a beach. (McGee was posted missing, and was my Dad's best mate and crewmate on ops – hence my involvement).

A young demobbed French Air Force pilot went to the Kommandant and as a fellow officer and airman asked to see the bodies and to insist that they would be buried with military honours. Given the climate after the assassination and hostage killings, this was quite a brave act. Even more extraordinary, at the burial, was the turn out of two hundred silent Quiberonnais bearing flowers. An amazing act of defiance

From then on, the graves became a focus of anti–German sentiment.

In 1942, Bomber Command became involved supporting The Battle of the Atlantic. August, 4th 1942, 460 Squadron despatched from Brighton 10 aircraft on Gardening (laying of mines from the air). A cloudy night with showers, the aircraft sortied independently, with take-off times from 22:00 through to 06:00. One plane was unable to carry out its sortie due to bad visibility. Another aircraft was not heard of after take off, and this was Wellington Z1422 (460/W).

The crew were:

The only crew member to be found was Thomas Hobgen, a native of Toowoomba, Queensland. His body was discovered on a beach by a young woman who placed flowers by his body before reporting the find to the Germans (62 years later at our Remembrance that same lady set flowers from the Community on Hobgen's grave).

Later in the month, another body was washed up on the nearby island of Houat. Unidentified, the body was buried on that small island, and re-interred alongside Hobgen at war's end. The headstone is the simple "An Unknown Airman...Known Unto God"

(Research in the Town's archive has proved this person to be Australian – and the matter of a rectified headstone is in hand by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission following consultation with Australian authorities)

It is tempting to think it might be one of Hobgen's crewmates. But "Known Unto God" is eloquent enough.

With the mining effort continuing, on 23 September 1942, 305 Squadron despatched three aircraft on Gardening. The two returning aircraft reported heavy-fire in the Lorient area and from shipping. The Squadron lost Wellington Z1476 (305/F) (in fact a lot of 305's machines were ex 460, being the rare Mark &Whitney engines)

The crew were:

The only crew member found was Antoni Ostrowski, who was interred next to the unknown airman. Liberation came in April 1945 (the town was too near fortified naval areas like Lorient). In the years since the sacrifice of these men has been regularly honoured and remembered. Looking ahead to the 60th anniversary of D–Day, Quiberon's museum felt that a special effort should take place. At the same time, a group of Brits were stirring the dust off of research done about ten years ago. Contacts were about to be made.

This message is just the chit–chat about the weekend, devoid of hard facts.

We jumped at our invitation. Our inviter, a retired school teacher, Elie Coantic, was quick to point out that it was a great honour for him and also the town for us to come, and we must understand that they were ordinary, lowly, folk. Sue and I forgot the basic French taught at school (a few years back now!), and Elie could only cope on the telephone with slowly spoken English. We were to get ourselves to Dinard Airport where he would pick us up.

Also attending was Alan Turner, who joined us en–route (and whom we had not met before), we disembarked from the plane in the brilliant sunshine that was to be the hallmark of our visit. Elie was a quite charming and pleasant man, and with Alan bringing up his memory of the French language we lapsed into a happy Franglaise, another hallmark of the weekend.

Ordinary, lowly folk? Well, us too… and we were immediately at home in Elie and Marie–Claude's house, our lodging for our stay.

The next day, Friday, with no effort too large or small, Elie drove Sue and I across Brittany to met up with the retired Mayor of a town that my dad had bombed, and with whom I had researched years back. The same day saw the arrival of Alan's son Richard and also the Son and Grandson of the British pilot (James and Tim Noble). James was born after his father's death, his mother remarrying, so this was quite a significant journey for him. His mother, still living, but quite frail, could not comprehend the whole business.

I was a stand-in for the McGee family, as Frank's sister is seriously ill, demanding her family's full attention.

Several meals later and the next day, Saturday, it was a sightseeing expedition to the town's weekly market and in the afternoon, a party of us, including journalists, set out across the Bay in three boats to the position of the recently discovered Beaufort wreckage. Here we conducted an informal ceremony, where a roll call of the missing was read out along with words of Remembrance in both English and Polish. A wreath was cast upon the water followed by single red roses and a minute's silence.

More sunshine, Franglais and meals took us through to Sunday and the formal ceremony at the cemetery.

A flagpole had been erected at the rear of each grave, and under a "guard" of the flag-bearing local veterans, the appropriate national flag was run up by each grave. The Unknown being represented by the French Tricolour.

A speech was made by the Mayor and also by Elie, also translated by Richard (that detailed the facts behind each loss). Each national anthem was played, followed by the French equivalent of The Last Post, a minute's silence followed by the most heart-rending recital by children of a 1942 poem that lamented the loss of liberty.

A Cessna light plane from the local aerodrome flew over and scattered rose petals. Following the ceremony, there was an informal reception at civic premises, where an artefact from the wreck was presented to James Noble. Following the reception, luncheon was proved courtesy of the Museum in a seafront restaurant, where we were joined by participants from the US-French D–Day ceremony held locally. Franglais had nothing on the medley of tongues heard over this meal.

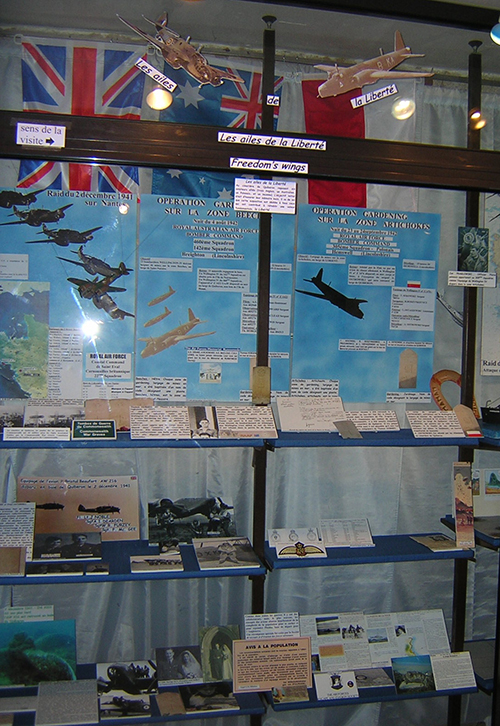

Afterwards, we retired to the Museum to preview their exhibition "Les Ailes de Liberte". What a splendid job they have done, Laurie; a true testament to our airmen. A large display cabinet held copies of photos (including Thomas Hobgen's) documents and models, maps and ephemera, set off by a manikin in full period flight equipment, the rest of the room given over to display boards. Most moving for us was to meet the old folk who remembered those days, Madame Lanty, Roger Vinet and Christian Moisson, who alas, is very ill.