Raid on Stettin: 29-30th August 1944

in J2 - Laurie Woods

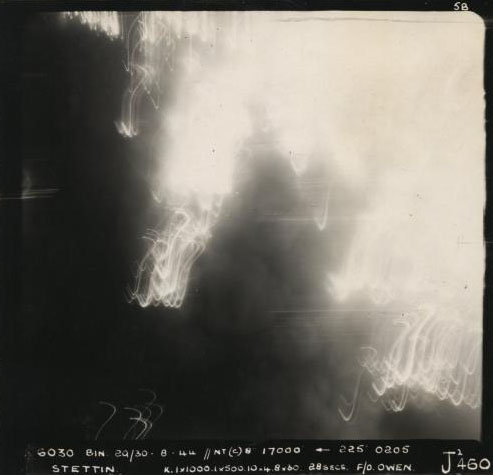

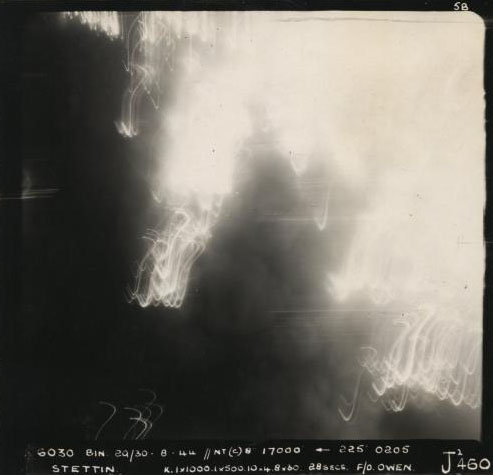

6030 BIN 29/30.8.44 // NT(C) 8" 17,000" <- 225° 02:05 Stettin K.1x1000, 1x500 10x4, 8x60 28 secs F/O Owen J2 460.

29/8/44 Stettin Incendiary through the roof, hit pilot on head and he dropped one wing, while phot was taken, then recovered and flew level again.

Railway targets, 29th August 1944, 02:05 hours, 17,000 feet.

Log book states – Bomb load: 1 x 1000 pounder, 1 x 500 pounder, 7 x 150 x 4, 7 x 12 x 30 incendiaries.

A description of the raid as appearing in the Bomber Command War Diaries, M. Middlebrook, C. Everitt:

402 Lancasters and 1 Mosquito of 1,3 and 6 Groups. 23 Lancasters lost, 5.7 per cent of the force.

This was a successful raid, hitting parts of Stettin which had escaped damage in previous attacks. A German report states that 1,569 houses and 32 industrial premises were destroyed and that 565 houses and 23 industrial premises were badly damaged. A ship of 2,000 tons was sunk and 7 other ships (totalling 31,000 tons) were damaged. 1,033 people were killed and 1,034 people were injured.

Not so Lucky Over Stettin

Excerpt from "Flying into the Mouth of Hell", by Laurie Woods:

ME649 AR-J2 the subject of Robert Taylor's "Strike And Return" print was our aircraft, skippered by Ted Owen for our fifteenth raid. Stettin was a long trip of 8½ hours in the air.

On 29 August we lifted off at 21:10 with a full load of 1 x 1,000 lbs. 1 x 500 lbs. 7 x 150 x 4 incendiaries, & 7 x 12 x 30 incendiaries.

It was a long uneventful flight over the North Sea with some heavy cloud, which lifted a little as we approached Denmark. As we crossed the coast we encountered some spasmodic ack ack. There was also some fighter activity, aimed at stragglers who had wandered off track.

Suddenly about a half a mile to port there was a bright pink glow in the clouds, and then we saw the reason, a couple of planes going down in flames. Whether it was a collision which seemed most likely or fighters or ack ack we didn't know, but we were happy we had not been any closer to where they went down.

Our scheduled bombing height was at 17,000ft. The briefing was to fly over Sweden at 17,000ft, as the Swedish gunners would fire their ack ack guns at us, but the shells would be fused to explode at 15,000ft. Approaching Sweden, where the lights were shining was a reminder of the days before blackouts, and the blackness that War had spread over most of the World.

As briefed, the gunners put on an impressive show with their guns. It was wonderful to enjoy the spectacle of ack ack guns blazing away, and the shells bursting just below us, and to know they wouldn't hurt us.

Passing over Sweden, we were routed almost due south, to approach the city of Stettin and the dock area, from the sea. This was wise planning, as we could make full use of our H2S to pick up the coastline and the river with the city off to starboard of our track.

After turning on to our new heading toward Germany, the searchlights, which had remained vertical stationary, were lowered to a horizontal position pointing on our track toward Germany. They waved up and down a few times, in a real heart warming gesture, as though they were wishing us God speed.

At 17,000 feet the cloud was closing in a little, and the Master Bomber nearer the target up ahead, ordered us to reduce height, with a minimum of 12,000ft for our bombing run. The message wasn't really concise and almost left the crews to choose their own heights.

Whether or not some of the crews did not get the message, or whether they ignored the instruction, to reduce height believing themselves safer at 17,000ft no one knows.

A Lancaster of No. 460 Squadron. Beneath the mid-upper turret is the dome-like housing for the revolving aerial of the H2S equipment. The rear turret is turned completely to starboard.

Often these late messages were ignored as some crews thought they were moves by an English speaking German to disrupt the raid in some way. For those crews who reduced height it was a recipe for disaster, flying in the lower layer when the bombs began to fall. So many in fact it seemed like a rainstorm showering down from above. We in "J2" did get the message, and immediately reduced height.

In the pale moonlight it was a magnificent sight to see the massive harbour with the docks on the western shore. Further to our starboard were the main city blocks. Many ships were lined up at the wharves, whilst several were either anchored or lining up for docking. It seemed as though the enemy was not really expecting a raid so far north. No attempt appeared to have been made to keep the shipping scattered in case of an air raid.

Approaching Stettin the fighters became very active, and a couple of Ju88s flew across from the port side several hundred feet below us. I watched them closely as they lined up on a pair of Lancasters. I was helpless, I wished I had some way of alerting the crews but watched helplessly as the fighters shot down both Lancasters, one blew up as the fusillade of tracers hit into him whilst the other burst into flames as he fell arcing to starboard. I reported to the skipper as a precautionary measure for all to keep a watchout. The fighters seemed to be hunting in pairs at a lower height than at the height at which we were flying.

Despite the long flight over the water, it was a gratifying sight to be approaching the target, with our plane nicely lined up on course to the target. The markers had gone down, and the bombs were commencing to explode. When flying into the target zone with the ack – ack bursting in our path, it always seemed to take an eternity before we were able to release our bombs on target.

What a picture. The searchlight beams, the fusillade of red, green and yellows ack ack tracers slicing up into the sky, the coloured markers being reflected from the water. Then just up ahead three more of our planes all within half a minute blown up by ack ack. How many more of our mates were getting the chop on this raid? They were being knocked out of the sky like flies.

It was apparent to the crews judging by our bomb load that this raid was designed to create as much fire damage as possible as we followed the first wave of the more heavily loaded explosive planes. Our load was mainly incendiary bombs.1/1000lb. high explosive, 1/500lb. high explosive. 7 racks of 4lb. x 150incendiary and 7 racks of 12lb. X 30 a much heavier incendiary load, than we usually carried.

The markers had gone down very accurately and I had guided Ted into a good position for our bombing run. I delayed the order to open the bomb doors, mainly because of the heavy ack – ack and also with fighters active in the vicinity. When I judged we were within 30 seconds of our bombing point I gave the order:

"Bomb doors open"…"Steady…Steady…Steady…Bombs gone…, bomb doors closed" "Steady for photo".

Suddenly there was a terrific crash, one wing dropped badly, then we came up straight. There was a loud rushing noise coming from the cockpit. I moved back quickly to see if the skipper was all right and when he appeared OK I resumed my duties giving the "photo taken!". Although the noise was still going on, and it had become quite draughty, everything seemed to be operating correctly.

I soon learned an incendiary had come through the roof hitting the armour plating shield behind the skipper, giving him a good thump on the head, and making him dizzy for a moment (hence the wing drop). The bomb then deflected through the blackout curtain hitting the navigator, Don Hudspeth, on the arm, driving his watch down through the arm and breaking his wrist. The arm was torn badly and later required twelve stitches. The bomb ended up on the floor behind the navigator, and fortunately it hadn't exploded.

The wireless/operator quickly wrapped it in his bag, and shot it out the photo flare chute. He afterwards said he got rid of it as quickly as he could before it had time to explode, and before he had time to get scared about what could happen if it did explode. He also stressed that he handled it, as gently as he could, and when he shot it down through the photo flare chute, he made sure it didn't touch the sides. At that moment two more planes exploded and went down on fire.

I suggested to Don Hudspeth our navigator I would take over the navigation home once we were clear of the target. He assured us he would be all right, if not he would call on me. The perspex canopy over the cockpit had been badly smashed, making it extremely cold and uncomfortable on the return journey, otherwise we were fortunate no other damage had occurred.

Safely on our course on the homeward route, we had a couple of close calls with fighters flying across our path, about two hundred feet below our height, but no actual attack as we left the target area. Approaching Sweden, the massive fires of Stettin could be clearly seen behind us. We were again waved over Sweden, this time the searchlights waving westward on our track toward England.

Over Denmark, the fighters were very savage for a short time. To get clear of the area more quickly the skipper clapped on speed. Suddenly the rear gunner reported a pair of Me 109s climbing to attack from below us. A quick corkscrew at full speed, a manoeuvre that delighted our skipper (ex–fighter pilot stuff) and the fighters disappeared.

A few minutes later we had another attacker firing as he climbed toward us from the port side. Again the skipper dived port, into the attacking angle at full speed, and the fighter's tracers passed harmlessly above and behind us. The skipper carried on corkscrewing a couple of times then ordering everyone to keep watch for any more fighters levelled off on our final leg for the run home flying at 20,000ft. We had just passed over Denmark and settled down for the long haul home.

The cloud was banking up ahead and we were encountering heavy turbulence when suddenly we were flying in a severe electrical storm. It was one of our roughest weather encounters, and Ted climbed as high as "J2" would go, 27,800 ft. where we were bouncing along, right on top of the cloudbank, and the storm partly underneath us.

The windows were being continually lit up by lightning flashes, with balls of blue fire playing round them. The propellers were also caught by flashes, which gave a real ghostly blue glow. Commonly known as St. Elmo's Fire is a beautiful, eerie form of atmospheric electricity that usually appears in stormy weather around airplane wings, windows, propellers and engines. During the thunderstorms, the air between the clouds and the ground becomes electrically charged, resulting in a discharge, the same phenomenon used in fluorescent tubes. This electricity is drawn to the closest conductor, in our case our plane.

After a couple of hours flying in very rough conditions, and still above heavy cloud, Ted decided to let down fairly quickly as we were getting close to base. We had always been advised not to fly if we had a cold. On this occasion I had a slight cold and suffered badly as I felt my eardrums were going to burst. After my complaint Ted held a much more shallow descent. Finally on the ground, it took me a couple of weeks to recover my hearing.

Our navigator, Don Hudspeth, was grounded until his arm recovered. We had been flying together for eight months, and it was a bad blow to lose one of our crew. It was also a blow to lose Don, as he was a terrific crewman, very obliging, a very good navigator, as well as being a hell of a nice bloke. For his effort on this trip he should have been decorated. F/O Don Hudspeth remained on 460 Squadron flying as a spare navigator and flew his last 11 raids with Sq/Ldr John Holmes. They were killed on a raid on Chemnitz on 6 March, 1945.

We had decided to volunteer for Pathfinders after the required 15 raids, but now with one crewman short on our 15th raid we did not qualify. Don did not fly with us again, and we had to finish our tour carrying a spare navigator each time. As we could only operate when a spare navigator was available, this extended our time on the squadron.

The raid on Stettin was very successful with 3 ships sunk and 34,000 people homeless. Coming back from the target P/O D.C.Balfour claimed the destruction of a Ju88 without the Lancaster having fired its guns. Five minutes after leaving the target the mid–upper gunner reported a Ju88 immediately below, intent on tailing a Lancaster ahead.

Balfour pulled the nose up to avoid a collision, but the wings touched and the fighter dived straight down. The rear gunner observed it burning on the ground. Back at the station, the port wing was examined and the top surface was holed and the wing itself dented.

F/O Neil Hudson, when 25 miles short of the target, collided with another plane, possibly a German nightfighter, which knocked out his port inner motor, bent the propellers on his starboard inner motor, and caused damage to the underbelly and bomb doors. Fortunately he was able to get the bomb doors open to drop his bombs, and then struggled home on two motors.

P/O Peter Aldred was not so lucky. His plane was attacked by an Me 109 on the way to the target when crossing the coast of Denmark. His gunner's managed to fight off the German. About 20 miles on, they were approaching the target at 17,000ft, when once again the gunners managed to fight off an attacking fighter. Descending to 12,500ft on the Master Bomber's orders, they were hit by three incendiaries from the planes above, badly damaging Peter's right hand and the plane controls. After bombing they were again attacked over the target by a fighter, but managed to evade him. With a great deal of difficulty the pilot managed to reach Sweden where they made a crash landing.

Some time later Peter Aldred was flown back to England in the bomb bay of a Mosquito which he thought was a bit of a come down from pilot, to just a load in the bomb bay. On his return to the squadron he described the Mosquito ride as the coldest, draughtiest and most uncomfortable air trip that he had ever had.

15 Lancasters were lost to fighters on this raid.

Back to Targets/Raids

Back to History

Back to 460 Squadron RAAF Contents

A Lancaster of No. 460 Squadron. Beneath the mid-upper turret is the dome-like housing for the revolving aerial of the H2S equipment. The rear turret is turned completely to starboard.

A Lancaster of No. 460 Squadron. Beneath the mid-upper turret is the dome-like housing for the revolving aerial of the H2S equipment. The rear turret is turned completely to starboard.