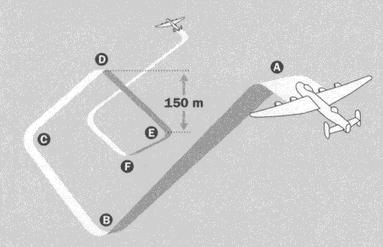

The "Corkscrew" manoeuvre

Written in the point of view of Laurie Woods, bomb aimer, DFC.

We (Ted Owen and crew) were assigned to "C" Flight at one end of the aerodrome whilst "A" Flight seemed miles away down the other end. The flights were separated or dispersed as a protection should we be attacked by enemy fighters or should we cop an enemy bombing raid. The crews from the different flights only met up in the mess at meal times, or for a special parade. To settle us down and to get used to the routine on the squadron we were rostered to fly a couple of cross country training flights in Lancaster "D2".

An air firing training was our next exercise in "J2" over the sea in the Wash area. The Lancaster had to attack a drogue being towed behind a plane and the gunners had to fire as the Lancaster flew past the drogue. We attacked several times until the gunners had used about 400 rounds and then we broke off the exercise to return to base.

On the return journey Ted asked me to take over the controls, to judge whether I could handle a Lancaster, after my limited link training. The Lancaster "J2", once I got the feel of it, responded to the controls well, and I felt it flew beautifully. The only trouble my lesson only lasted about ten minutes.

Our next flight was a five hour night cross country in "A2" taking off just before midnight. Having successfully carried out this exercise, we were declared ready and we were rearing to go.

In order to dodge an enemy fighter the corkscrew was included in our training, and led to some pretty hectic moments for other members of the crew. The pilot was the only member of the crew with a seat belt. Normally the corkscrew would be a very violent dive to port, or starboard, most often with no warning, and crew members were often suspended from the ceiling then flung violently down to the floor, as the plane came out of the initial dive and climbed away on the next leg of the corkscrew. There is on record that "S" Sugar, from 467 squadron (Now an exhibit in the Hendon Museum) returned from the raid on Revigney, in July, 1944, with 137 rivets missing from one wing, possibly as a result of a violent series of corkscrews during the many attacks by German fighters on this particular raid when 23 Lancasters were shot down, mainly by fighters after leaving the target.

There was a measure of excitement in the crew when we were allocated K2 "Killer" as the plane we would generally be flying. It was the plane's 34th raid, and our wish was that she would do a hundred trips, and in the process carry us safely through our tour.

On the side of K2 "Killer" was a big yellow swastika with a hand holding a dagger, the dagger piercing the heart (red) of the swastika, with red blood dropping out of the wound. Underneath were the letters "Killer" in yellow with red blood dripping off the letters.

The nose art design on K2 "Killer" was very striking, having been drawn up mainly by Bill Gourlay, navigator from Launceston, Tasmania. Bill flew in Vic Neal's crew and they had commenced flying this brand new aircraft on operations on 15th March 1944 on a first raid to Stuttgart, 2nd and 3rd to Frankfurt, 4th to Berlin, and 5th to Essen. What a blooding in operations for any aircraft or crew.

Vic Neal and crew flew 23 trips in K2 "Killer", whilst Bill Gourlay and crew flew an extra "Killer" trip with W/Cdr Douglas, leaving their poor pilot to sweat it out in case he lost his crew to the squadron commander. From Flying Officers, Vic Neal, Pilot & Bill Gourlay, Navigator, we had a good report on what to expect, as they described to us their experience in "K2" on the raid to Mailly Le Camp, on 3rd May 1944. They both felt lucky to have escaped any serious problems, and thought the raid was a bit of a mess up. They also told us about the incident when getting ready for a raid on 18th April 1944 where they were lucky to come away unharmed.

Vic and Bill also got an opportunity to fly in the now famous "G" for George (which is now the star attraction in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra). When they were all bombed up and ready to go in K2 on the Nuremberg raid, when number 3 engine was missing revs and at the last moment they were changed to the spare aircraft which happened to be "G" for George.

Our next raid was the military installations in the Caen area on 18 July in K2 "Killer" with take off at 0335am.

Flying in over the Normandy beachhead was always an awe inspiring sight. The ever changing parade of ships, roughly 1,000 of them, many of them coming and going, whilst other ships had flotillas of landing craft, either clustered round the ships, or shuttling back and forth to the beach.

We were being escorted by a swarm of Spitfires high above us and also a few flying quite close to the stream of bombers. The morale boosting effect of some protection from our fighters was welcome. However the fighters were soon forgotten as we came in over the fleets of ships. Over the beach at dawn, we split into four sections to raid military installations in separate sectors, almost like a dawn patrol, except that we stirred the German defences to blaze away at us with the ack ack. We were directed down to 3,000ft for our bombing. At this low height, we realised why the safety bombing height for 1,000lb bombs had been set at 4,000 feet.

Flying through the target, was an extremely rough passage because of the blast effect from our own bombs. With so many explosions, the planes were flying as though someone was hammering at them from underneath, trying to shake them into little pieces.

One of our squadron Lancasters from "C" flight returned to base with a nosecone from one of our own 1,000lb. bombs embedded in his starboard outer engine. This was reported as one of the most useful army support raids carried out, and severely affected a German Luftwaffe Division and a Panzer Division. They were caught at breakfast time and hopefully ended up with either a cold breakfast or no breakfast at all and something apart from cream in their coffee.

On our way out we were dodging in and out of the incoming stream of bombers. With over one thousand bombers on target it was an amazing sight to be dodging the incoming bombers as we were coming out of the target area. We cursed such inefficient routing of bombers back through the stream of incoming fully loaded bombers. Such inefficiency could have caused a real catastrophe but miraculously there did not seem to have been any collisions

Our bomb load, was 11 Х 1,000 lbs. and 4 Х 500 lbs.

From a later report on these raids Bomber Command with 942 aircraft in the four raids had dropped 5,000 tons of bombs on the German emplacements in just a few minutes whilst the Americans also bombed the targets dropping another 1,800 tons to add to the damage.

The same night taking off in K2 "Killer" at 2300 for our ninth raid on oil installations at Gelsenkirchen, had us realising how tired we were. We had taken off in the morning at 0335 which meant we had started our preparations and meals before midnight, and yet here we were again airborne at 2300 hours. After take off we climbed for a height of 12,000ft at our rendezvous point over Mablethorpe.

We had on board our first loading of the block buster 4,000lb bomb, known and easily identified as "Cookie", The total bomb load was 1 Х 4,000 lbs. and 16 Х 500 lbs. filling all possible bomb stations. The 4,000lb Cookie had a thin casing, which increased to four times its normal size then exploding. This factor created the blast effect. It was also dangerous, as had been proven when the bomb dropped from a plane to the ground in the dispersal. The bomb had exploded wiping out the plane and also damaging adjacent planes.

If hit in the bomb bay by a piece of ack ack, and the cookie exploded there was nothing left after the blast. The crew was always very happy when the Cookie had been dropped. It always felt so much safer, not having it riding just under our feet, with only a thin aluminium floor between the bombs and us. This was our first block buster "Cookie". It was for maximum blast effect in the oil installations, and hopefully this would cause a lot of property damage.

It was also our first raid into the Ruhr Valley, (commonly referred to as "Happy Valley" and you were happy to survive a trip through), we had been briefed to fly on a route avoiding bad ack ack locations.

Flying a circuitous route from Mablethorpe to 53°00'N 03°00'E to 52°35'N 04°35'E to 52°20'N 07°05'E then the target D (marked in our log books thus) then 51°38'N 06°20'E to 52°20'N 05°20'E to 52°20N 03°00'E then Cromer – Mablethorpe – Base. These different courses were set up hoping to confuse the German defences and the fighter controllers, for a little while. We always hoped that the ploy would work and keep the fighters away, but we seemed to attract fighters like bees to a honey pot. It was a deadly guessing game. Which way was the raid heading, and where was the best place for the fighters to intercept the raiding bombers? It was a constant battle to see who could outwit the opposing forces, and gain an advantage.

We had been told to expect a concentration of about 300 searchlights, with a possibility of around 500 ack ack positions. The numbers didn't mean very much, excepting it sounded like, and turned out, a terrific amount of defences.

How can one describe flying into a rainstorm of ack ack shells bursting all round us, of violent explosions in the air, of explosions on the ground. The fighters and heavy flak 105mm and 128mm guns, bursting just around and above us as the gunners got onto our height. The radar–guided 88mm guns which fired predicted flak and could pick off individual bombers at considerable heights. The lighter flak guns of 50mm, 37mm and 25mm, with their red green and yellow tracers arcing up toward us as though it was water being sprayed from a fireman's hose. All guns being fired as fast as the gunners could load them. It was quite a sight as rings of shock waves, came up out of the inferno on the ground, as the Cookies blasted many into eternity. These shock waves were like circles of shimmering light, ever widening, rising through the smoke and fires.

I was absolutely petrified. How could anyone survive this fusilade of death and destruction? Someone had said when you are really frightened get your mind on to something else. I started saying to myself

"Into the valley of death, rode the six hundred, guns to the right of them, guns to the left of them".

"Yes, I'm thinking, what about the guns below them, and the ack ack shells curving upwards at my belly".

There goes a plane down in flames to port and another one underneath us. I grabbed my parachute putting it between my legs, and lay on it, at least perhaps I could preserve my manhood. This felt fine, and so my rolled up parachute was used on many more raids, for my personal comfort and protection.

With perhaps five minutes left on the run into the target, all sorts of jumbled thoughts flew in and out of my head.

"The Lord is my shepherd I shall not want, He leadeth me beside still waters".

"Into the valley of death rode the six hundred, and he will protect us".

There go another two planes. They must have collided in this air alive with flak.

"Surely goodness and mercy. Have mercy on us".

How could we possibly survive? The flak was unbelievable.

I was shaking like a leaf and my thoughts were jumbled. I was beginning to wonder if I could drop the bombs because of my shaking. This waiting and watching and seeming to crawl up to the target was dreadful. My thoughts were becoming more jumbled the closer we got to bomb dropping. Suddenly there was a blinding flash less than 100feet above us accompanied by a shocking blast which shook our plane and then the mid–upper's voice: "Gawd, he's blown up, and his engine, white hot, just missed me as it went down between our wing and our tail plane!" Ted had swung hard, when the explosion occurred and this had possibly saved us from the engine, which just missed the fuselage of our plane.

It was time to bomb and suddenly, after this violent manoeuvre threw me against the side of the plane and the blast of the explosion, I was as cool as a cucumber.

"Bombaimer to Skipper, bomb doors open.

Left, left, 20 degrees, Steady

Right 5 degrees, Steady, Steady, Steady, bombs gone. Close bomb doors.

Hold for photo; photo, photo, photo taken".

I always had the bomb doors open for the least possible time. I felt safer with them closed.

The fires and the explosions on this raid were awesome and unbelievable. On the run up to the target there was a terrific explosion and flames shot up 4/5,000 feet, so bright that the searchlights were blotted out momentarily. It appeared almost like day for about fifteen seconds. A smaller explosion, a minute later, indicated considerable damage had been done to the oil storage. As we flew out of the target area the German fighters were diving in among the bombers and the tracer bullets were flying in many directions. On the ground the fires were lighting up the whole area, and it was satisfying to see we had hit the target area good and hard.

Everyone was on tenterhooks with reports on fighters too close for comfort but, fortunately for us, they were not attacking us. Tracer bullets were flying from some of the planes and we saw a couple of fighters firing their cannon shells into one unfortunate bomber. After receiving two or three sustained bursts of fire the plane suddenly blew up, heeled over on its side and went down in flames. It all happened so quickly and the shell busts on the plane were so deadly that the crew didn't have a chance of parachuting.

On our return to base, as we climbed into the crew bus to be taken to interrogation, I heard one bright spark say "The flak was so thick we could have put our undercart down and landed on it". I was in silent agreement. Another crewman passed an opinion that those German fighter pilots sure had guts as they risked being shot down by their own flak over the target in their hunt to get a shot at one of the bombers, as well as risking being shot down by one of the bomber gunners.

Of course we all knew that over the target in the bombing run flying straight and level the bombers were at their most vulnerable. However we would raise our hats to the German fighter pilots and to their courage.

When the aircrews came into the light at interrogation and again in the mess, they had a queer look about them. It suddenly struck me that their cheeks were sunken, and they were sullen with none of the usual spark and light chatter. Their eyeballs gave the impression of sticking out of their heads, and they were listless and moved like old men. The two raids took 27 hours without a rest or sleep. The continual roar of the engines hour after hour, the nervous tension, and long hours were having their effect.

The next morning making an inspection of our plane in daylight, Sgt. Bill Young and Cpl. Jack Hill (Melbourne) "K2" chief groundcrew climbed into "Killer" and came out looking very subdued when they discovered most of the top of the pilot's canopy had been blown out by the explosion. With 34 individual holes in the top of our plane Bill Young's comments were "Jeez what happened last night, you poor buggers, don't worry, we'll soon have her fixed up like new!" and they wanted to know what had happened. Miraculously no one was injured, except for the awesome fright of our young lives.

On the return, many airmen didn't attempt to get food but headed to their rooms, where they just flopped down clothes still on, too fatigued to undress and get into bed. Most aircrew found it impossible to sleep after these raids. The mind seemed to go round in never ending circles, and we were only able to doze. The deafening roar of the engines was still with us for many hours. Still in our clothes, after 3 to 4 hours dozing, some of us drifted back to the mess for some food. Others had a pick at the meal. We all drank a lot of fluid because flying above 12,000 feet, we had to use oxygen which had a very drying effect on our bodies. We then usually headed back for a shower, mainly looking to moisten our bodies. Only then were we able to lie down and get some sleep.

Without oxygen at 20,000 feet, we were told we could only survive for four minutes. Therefore its use was absolutely necessary. Crew members always had to be alert at all times, to make sure none of their crewmates were suffering from lack of oxygen.

When asked by the new crews what it was like over Germany, this raid became our measuring stick. "Wait until you raid Gelsenkirchen, then you will know how tough it can get", became our standard reply.

Speaking with Bert Uren, navigator in P/O G. Stone's crew he said they had Group/Capt. Hughie Edwards as their skipper on the Gelsenkirchen raid and the crew thought they were extremely lucky to survive. On the run up to the target almost on the point of bombing the mid upper gunner reported a bomber just above and he felt they might be hit by the bombs which he could see in the open bomb bay just above them.

Group/Capt Edwards in his true "press on regardless manner" ignored the warning and when the 500lb bombs were released one bomb just missed the leading edge of the wing and the next bomb just missed the trailing edge. Almost immediately a plane just in front of them received a direct hit and with a blinding flash blew to pieces. It was so close they flew through the debris from the plane which had been blown apart. How lucky can you be?

On another raid P/O Stone and his crew were flying "J2" which was in the next dispersal to our "K2". Without warning when closing the bomb bay to commence taxying in readiness for take off, their cookie dropped to the ground. Bert Uren, the navigator, suddenly realising he was alone in the aircraft went to the door to find out what was happening and swears the majority of his crew were 500 yards away and running fast enough to win the Stawell gift. A ground crew man standing next to the undercarriage said 'Don't worry matey, if she was going to blow up we'd be in heaven now".

We saw all the commotion and our skipper did the next best thing. He opened up the motors on "K2" and we shot out of dispersal like a scalded cat, much to the amusement of the crew with comments, "Hang on skipper! We need a bloody runway and a green light before you think of taking off!"

It wasn't until 0005 that we lifted off to raid the railway marshalling yards and a triangle junction, at Courtrai. It had been a long day. Over the target we were not happy when three fighters attacked us.We had a fighter flare dropped almost on us, and then a JU 88 attacked. The flare must have blinded the German pilot as he came in. Ted had dived K2 "Killer" to port and the centrifugal force had me frozen in space almost suspended under the front turret and it flashed through my mind I was being thrown about like a puppet on a string. We were diving fast to evade, when the JU 88 suddenly appeared about 30 yards off our wing tip, he must have been just underneath getting ready to blast us, or perhaps there were two of them hunting as a pair, but we didn't know and we didn't wait round to find out

He would have been a real sitting shot for our gunners, but it happened too quickly for them to swing their turrets round. He broke off the attack, and disappeared.

Suddenly another JU88 attacked from starboard astern. The rear gunner reported, "Enemy fighter attacking from starboard side, prepare to dive starboard. 600 yards––––––––500 yards ––––––prepare to dive –––––– dive!"

This time Ted dived at the same time ordering 15˚ flap, undercarriage down, as he simultaneously reduced power to idle. The fighter overshot us like a rocket, almost hitting our wing, and disappeared into the night. Miraculously, after another attack and one short burst, which went wide, no further shots were fired and the German fighters disappeared as quickly as they had appeared.

The target was absolutely devastated, with a terrific amount of damage to the railway yards. It was estimated that it would take many days before any trains could get through. Bomb load, 11 Х 1,000 lbs. and 2 Х 500 lbs.

On our return to base, our area was blanketed in fog, and despite all crewmembers keenly searching for a break in the fog or a sight of the ground we couldn't sight anything and were diverted to Lindholme. Only about six planes managed to land, before the fog closed in on Lindholme and the remaining planes still in the air were diverted to Leicester East. The fog on occasions closed the dromes so fast we were getting a little bit worried. What would happen if we were not able to land. What then? Others were not so lucky, as 9 Lancasters were lost. We went to bed after supper at 6am and were called at 12 noon. I navigated home, while Don our regular navigator climbed into the rear turret to get a feel of what it was like on the tail end of a plane, and to see the scenery. After formalities at base and a meal we climbed into bed for more rest and sleep.

Awakened at 1830pm and dressed at 2030pm. Frank, Steve, Peter and I walked to the village hoping to find something to eat, but no luck. On return we were lucky enough to get some food, and a cup of tea, in the mess. Then back to bed catching up on sleep.

From this raid P/O R.H.Jopling and his crew failed to return.

Jopling was shot down on this raid, and had some fun evading capture after baling out over Dixmude.

Harold later told me of his experience when approaching the target.

"He was flying in the front group enjoying the flight with no flak, and no fighters, when suddenly all hell broke loose, with flak bursting all round. Hit by flak as the bombs dropped, he was attacked by a JU88 with upward firing canons, their shells exploding in the starboard wing knocked out his two starboard engines.

With half his starboard wing and tailplane gone and fire in the wing, the wireless gone through the roof, the navigator's table collapsed and crew members wounded, he lost control of the plane at 12,000feet as it commenced spiralling down to earth.

He fought desperately to regain control and at 2,000feet with partial control and with the remainder of the starboard wing glowing white hot and only the port outer motor operating he ordered the crew to bale out. The mid–upper gunner froze in the back door, and to speed his exit from the plane, the rear gunner gave him a kick in the backside to send him on his way.

The bomb aimer had difficulty in opening the front escape hatch so jumped on it and as it gave way he went out with it.

Jopling, when boarding the Lancaster at base, had foolishly thrown his parachute inside the door instead of carrying it up front to the pilot's position, and when the wireless operator, Sgt Don Annat, reported all crew were out and it was time to go, Harold told him he couldn't because his parachute was back just inside the rear door. The wireless operator somehow scrambled back over the debris and the main spar, difficult to negotiate at any time, collected the chute, came forward and clipped it on Harold's chest and said "Right let's go, Boss".

Jopling holding the stick hard over to lessen the spiral, eased himself, with a great deal of difficulty, out of his seat, and then following the wireless operator made a flying dive out the front hatch, which was a feat as the escape hatch was not particularly easy to negotiate at the best of times. Estimating his height at 700 feet he was extremely lucky that as his chute opened his Lancaster exploded and with the force of the explosion he was blown much higher. The minimum safe height for baling out was 3000 ft.

Landing safely in a village he quickly cut the top off his flying boots, got rid of his parachute, and was just in time to join a German troop who were looking for him so he joined them looking for him. They spoke to him in the dark but he just gave them a wave on and seeing a lane to one side, he ducked down the lane, and as soon as he was alone, he ran for his life. Once clear, he walked at night and hid during the day. He found a vegetable patch where he lived the next few days on raw carrots, raw potatoes and his escape kit.

While he was walking he met an American flyer, a Captain who had commanded a Flying Fortress squadron. When asked what happened the Captain stated his Fortress was running short on fuel and presuming everyone was also getting short on fuel he ordered the whole squadron to bale out. Harold got away from the American as quickly as possible.

On arrival at Ypres he was contacted by a member of the Belgium underground forces and taken to a café where he was given what he described as "a beaut feed of bacon and eggs".

The Belgian underground people took his uniform, dressed him in civvies and took him to a farmhouse near Boezingst, where they kept him under armed guard while they checked to make sure he wasn't a German masquerading in order to trap them. When they were satisfied he was taken by bicycle to Chateau Zonnebec where he lived in the upstairs of a farm shed. He had to haul the ladder up while he was up there.

Each evening the baroness would arrive with the meal of the day and from his hideaway he could watch the Germans doing their drilling, as they were in occupation of the chateau, using it as their headquarters".

A summary of a post war report from Mr Oscar Joos, 26 rue Camelinat states:

"On July 20 1944 after the bombardment of Courtrai, we have taken an Australian, Aus 410065 Pilot Officer Jopling, RAAF Not being well he was also nursed by Dr Bolvin.

Our district was always searched by the Gestapo who have taken several patriots; so we are anxious about our Australian and we used two hiding places, one for the days under the weaving looms, the other for the nights in a spring mattress, hiding places quite undiscoverable. During the clearing of the Germans, this officer, helped by an American Captain ,rendered us great service in putting in front of our house a big S.O.S. Allied aeroplanes saw it while we were shaking an English flag to obtain aid. – we went to our place of fighting with the Australian who seeing the first English motorcyclist went to the Anjot Staff to explain the critical situation at Halluin.

Mr Joos, member of the resistance, fighting in Lille Street, brought back home with him, the English cyclist, a doctor and his orderly. Tanks had been asked for Halluin, they arrived the next day and we saw our Australian on the turret of the first tank. After the liberation, Mr Joos, took the Australian dressed in a new suit, to the Major Staff at Lille, as well as his friend, Kenneth J. Butler, Engineer, taken by Mr Oprien Nollet a retired policeman 238 Lille Street, Halluin"

Jopling was then taken to Menin where 3 girls took him to the French border and engaged the guards in a flirtatious discussion thus allowing him to cross. Two of these girls were subsequently caught and later shot for stealing ammunition for the villagers after the resistance had taken on the fleeing Germans who were in full retreat. Jopling joined the resistance in some forays, whilst he was in the area. He finally got through to Lille where he joined up with the Allies and before his repatriation was organised he had the pleasure of hanging out of the top of a tank as they drove through the village where he had spent some time. He was then taken by a British truck, picking up several evaders on the way, to Paris.

Arriving in Paris they were stoned by the locals who at first believed them to be enemy. Next day they were airlifted back to England in a DC3.

On returning to 460 squadron Jopling pressed for a decoration for the wireless operator Don Annat. His action, at an extreme risk to his own life, in going to the back of the Lancaster to retrieve his skipper's parachute deserved an award. It had been a foolish action to throw the parachute just inside the entrance door and leave it there when boarding the plane. It almost cost him his life.

Jopling was asked "who else witnessed this action by wireless air gunner Annat" but could only answer truthfully that as all other crew members had already bailed out it left only him and Don Annat to bear witness. His claim was disallowed. As Jopling was listed by the Gestapo he was not allowed fly again over enemy occupied territory".

From Peter Firkins book "Strike and Return":

The mid–upper gunner, Sergeant Mills, was not so fortunate as the following account of his experiences reveal:

"My Lancaster was hit by flak over Belgium when we were returning from bombing Courtrai and we all baled out successfully. It was about 0130 hours when I came down and quite dark, I landed in the centre of a cornfield near Roelcappelle, about 10 miles north of Ypres.

The corn was about 4 feet high and I pulled in my parachute and discarded my harness which I hid. "Wanting to get to France as soon as it was light I made off south–west, crawling through the fields and walking by night. By dawn the following morning I reached a cement road which led roughly south–west and wanting to make some speed I followed it. It had rained incessantly the night before and I was wet through.

"After about half a mile, at a crossroads, I came to a statue to the 18,000 Canadians who were the victims of the German gas attack during the last war. Here I made my first contact, a man who was clipping the bushes of the large garden surrounding the monument. "In English he told me to avoid main roads after the curfew and I stayed with him until evening, when he brought me some food, tobacco and coffee.

He showed me a secondary road which was not on my escape map and which led to a small place on the French frontier.

It was getting dark when two Belgians on bicycles caught up with me and took me to a small wayside café. They said they were evading being sent to work in Germany, and took me to a disused barn about three–quarters of a mile away saying the 'Captain' would come to see me in two days' time." I slept there and they brought me food and civilian clothes.

On a Monday, about four days after my landing a taxi drew up to the other side of the road and two men stepped out and went to the café leaving the driver behind. A child came from the café to call me and I went across. The cafe owner introduced me and the two men took me in the car. I was taken to a house about a mile from Ypres on the main road where two sisters of one of these men lived. The other man was the 'Captain'. They gave me some better clothes and food, and the two men took me in the taxi to Ghent.

I spent a week in various houses and cafes and was then taken back to the house near Ypres where I stayed for about three weeks. The two men often took me out in the taxi to see various friends of theirs and I gather they used to ask for money. At about 0400 hours on 21 August 1944 I was woken by the two men who told me to get up quickly as we were all going to Dunkirk then to England. A taxi was waiting and we drove off, but a mile down the road half a dozen German military police were waiting for us.

We were taken to the German Field–Gendarmerie H.Q. at Ypres and about two hours later the café proprietor was brought in, badly beaten up. The Germans tried to make him say he knew me and also tried to get my admission that I knew him, but without success. Various other people that I had called upon were also arrested. Either the man at the Canadian memorial or the 'Captain' were indiscreet or unfortunate, or else they could have been double agents".

Mill's escape, although unsuccessful, revealed the hazards and the nervous tension involved in these bids, and also the risks taken by the Resistance Movement members themselves.

A similar situation befell Flight Sergeant Don Dyson, shot down when returning from Hasselt on 15 May. After baling out he landed in a lake, and getting ashore, he walked for days in his cold wet clothes before making his first contact. After numerous moves he finished up in Brussels, awaiting the arrival of the allied forces.

When Dyson walked into the Boomerang Club in London a few days after his liberation, one of his former ground crew was standing just inside the door. As nothing had been heard from McLeery's crew since their loss, the ground staff man thought he was watching Dyson's ghost. It was some time before he was assured all was well.

On the 2 December, 1943 taking off at 1650 hours they headed for Berlin in "G" George, and due to inaccurate wind forecasts the bombers became scattered, they were ½ an hour late over the target. The Germans had identified Berlin as the target 19 minutes before Zero Hour and many fighters were waiting. Out of 450 aircraft a total of 40 were shot down, 37 Lancasters, 2 Halifaxes and 1 Mosquito. 460 (Australian) Squadron lost 5 of its 25 Lancasters on this raid including the aircraft in which two newspaper reporters were flying. These were Captain Creig of the Daily Mail and Norman Stockton of the Sydney Sun. The body of Mr Stockton is buried in the Berlin War Cemetery.

On 16th December 1943, Ken Godwin in "D" Donald on return to base found the fog had reduced ceiling visibility to approximately 200ft. and flying too low in keeping under the fog base, he crashed the aircraft with several injuries to the crewmen. Barrie Beaumont was gashed about the face, and in hospital when smoking he could blow the smoke out of three holes in his nose. He didn't fly with Ken Godwin again but was navigator to Tony Willis who had returned to 460 squadron to do his 2nd tour. After our navigator, Don Hudspeth, was grounded with a smashed arm from our raid on Stettin, Barrie did five trips as our navigator to complete his tour. The engineer in Godwin's crew, after the crash on the 16 December, 1943, was unable to carry on because of his nervous condition and was transferred to Transport command, where he was engaged in ferrying aircraft across the Atlantic.

Vern Dellitt in recalling their being shot down on the Leipzig raid had this to say: "On 19 February, 1944 in "H" Harry they were detailed to raid on Leipzig. Taking off at 2330 with a 4,000lb cookie bomb and the rest, 8,000lbs of incendiaries, after take off we climbed out and back over Lincolnshire, to reach 12,000ft before setting course and still climbing on track to reach the operating height when crossing the German Coast just South of Bremen. The course was then set to eventually, with a couple of corrections, bring our plane to a point 35Ks North of Hanover, where we were to change course for the run into the target. The German fighter controller had only sent a small force of fighters to the mine laying off Kiel and recalled the remainder of his fighter pack to attack the main Bomber Force as it crossed the Dutch Coast. The bomber stream was under attack all the way from the coast to the target and back. From a force of 561 Lancasters, 255 Halifaxes, 7 Mosquitoes, 44 Lancasters and 34 Halifaxes. The Halifax loss rate was 13.3% of those dispatched and 14.9% of those which reached the enemy coast had turned back.

The Halifax 11s and Vs after this raid were permanently withdrawn from operations to Germany. It was a moonless night, with scattered light cloud, as we flew closer to Hanover, Suddenly the bright cleaving shaft of searchlights and bursting flak lit up the sky indicating we were close to Hanover. Ahead and over to starboard, a bomber blew up and a second later another bomber received a direct hit and burst into flames as it arced over into a death dive toward the ground. Mike Wiggins our stand in RAF navigator ordered a change course to 135° in one and a half minutes time. Our pilot Ken Godwin had only just repeated the course change to the navigator when a long stream of tracer bullets came pouring through the fuselage surrounding me in a ball of fire as they flew all round me on their way out into the blackness of the night in front of the plane. A German fighter had riddled our plane from tail to nose, and setting us on fire, in a couple of short bursts of canon and machine gun fire. It was so dark it would have been impossible for the fighter pilot to see us without some form of radar aid. From the bomb aimers position where it was normal to see the searchlights and ack ack out in front of me it was a weird and frightening sensation to have these streams of tracer pouring out of the nose of our plane on every side of me. They were so close the guns seemed to be shooting right over each of my shoulders.

The skipper immediately started checking on each member of the crew. As the bomb aimer I immediately reported OK and the engineer likewise, but the navigator was busily fighting a fire in his compartment and curtain. There were no further replies from either of the two gunners nor the wireless operator. The engineer immediately went to the navigator's aid fighting the fire. The skipper became concerned at the glare around the back of the plane. As the plane appeared to be well on fire and starting to go into a dive and with the incendiaries loaded in the bomb bay starting to burn he gave the order to prepare to bail out.

I released the escape hatch a 23inches wide x 26 inches long, often called the parachute hatch, but it stuck and I had to give it a good thump with my boot to release it. I had got rid of my oxygen mask and headphones so that I had nothing round my head which could get caught and possibly choke me, I was almost ready to jump, when suddenly someone behind jumped into my back. I was forcibly thrown through the escape hatch, my legs caught on the rear edge of the hatch and I was swinging from the plane in the slip stream. Thankfully my legs were grabbed and freed, sending me plunging down into the blackness.

I had left the plane somewhere around 20,000feet and I was a little fearful lest my parachute didn't open. Being somewhat dazed, from my pummeling exit from the plane, I let myself fall for some distance before pulling the rip cord and had a moment of panic, which seemed like hours, until my chute opened.

It seemed ages as I floated down when I saw our plane a mass of flames heading earthward. I watched fascinated as our plane hit and exploded splattering the remains all over the ground. Blue Hennessy, (w/op), Jack Morris, (mid/upper gunner), both of Sydney, Hake Clarkeson, (tail/gunner) Wiggin, and Sgt Wood, (engineer) RAF all perished in the plane. Ken Godwin, pilot, escaped by parachute but was murdered on the ground. Mike Wiggins, navigator, and myself, Vern Dellitt, bomb aimer were the only survivors.

Descending through the layer of cloud in the descent was a grim experience, very bumpy and swirling air currents had me swinging almost horizontally under my parachute canopy. The ground came up very quickly and I was lucky to land on my feet. My chute, collapsing in a heap, pulled me onto my back. I gathered them all up and hid them under the snow near a hedge. Wearing only one flying boot and two pair of socks on the other foot I made my way in the dark across the fields. It was so dark I was almost into farm houses before I saw them. The barking of a couple of dogs had me worried that they would raise an alarm. The rough frozen ground made progress very difficult especially with only one boot. To help preserve my mobility, as my unbooted foot was suffering and I was frightened of frostbite on my feet, I kept swapping the boot from foot to foot,

Using the small escape compass I traveled in a Northerly direction. After what seemed hours I heard the thundering noise as the bomber fleet, heading West, passed overhead. It was a most depressing moment to think that I should be up there heading back to a crackerjack breakfast and the comparative comfort of a warm bed, instead of in enemy country, where I was feeling my plight badly. The cold and already feeling hungry was giving me a fit of the miseries. I was extremely tired and although I lay on the cold hard snow I could not sleep. Deciding to keep moving I carried on and came to a single track railway line which I followed for some miles, hiding to one side as each train came by.

At daybreak I spotted an old shed on a disused target range pit where I hid during the day. I slept fitfully on a piece of old Hessian spread over a rough seat, but it was too cold, even the water in my little bottle had frozen. From my silken escape maps I planned to head for Rostok where I hoped to get a ship headed to Sweden. As soon as it was dark I headed out and later in the night I crossed over a marshy section which was covered in ice. Several times the ice broke and I got my feet wet but I carried on and finally reached high firm ground. I kept moving all night to keep warm and was lucky at it got lighter to spot an old horse stall out in the open, seemingly miles from anywhere. I entered and was soon asleep.

About three hours later I was awakened by a couple of farm hands, who thought I was an American. They walked me about a mile to the neighboring village, leaving me at the Burger masters office. I was guarded by a soldier, until later in the day, a covered truck in the charge of an officer came to collect me. Despite the fact that I was ravenously hunger and pleaded for food I did not receive any. I was taken to the local fighter dome. A number of American airmen had also been brought there and we were being interrogated. Apart from my name, number, and rank I would not answer any more questions and I was left alone while the interrogating officer concentrated on the Yanks. Information that a couple of them gave was in my opinion more than what they should have given. The interrogation was interrupted when they brought in our navigator, who was visibly the worse for wear showing cuts and bruising about the face and head suffered when escaping from our burning plane.

We were talking with a Yank when a high ranking fighter pilot strolled in his chest covered by several decoration ribbons, signifying his large tally of allied planes shot down. He had been educated for several years at an English public school and spoke perfect English with no trace of an accent. He had spent two years in several parts of America and after chatting socially for a while the yanks realized he had shot them down. They discussed the method of the attack and their defence. This good natured sporting discussion on planes, equipment, ammunition used was an example of efficient, deceptive interrogation socially disguised. After a few moments the officer fighter pilot left and we were taken to another compound and locked in a room. Here we were given some rough food which had been cooked by French prisoners, who did their best to make the food as appetizing as possible. We had an impromptu party with one of the Yanks acting interpreter and some song singing.

Next day the air raid sirens started wailing about mid–day and the Luftwaffe went into action. Motors started coughing into life, as the ground crews warmed up the fighter plane motors. In a matter of minutes, the pilots were gunning their motors, and taking off straight from the dispersal area, in all directions, regardless of wind direction. As they reached a third of their take off run another lot were starting their take off in a direction 90° from the earlier planes, and when airborne another flight was taking off in the opposite direction underneath them. Me 109s, 110s and Fw 190s approximately 100 had taken off in a keen, wild control in about 15 minutes. Once airborne they flew around the drome formatting at various heights and set off climbing fast in the direction of Hanover. An American raid was in progress with Fortresses escorted by fighters, and we could hear the bombs exploding and the guns firing continually. The sound of the screaming engines of the diving dog fighting planes was music to the ears even though it was in deadly earnest, it was a grim reminder of the hell fire we had experienced such a short time before. The German fighters, short on fuel, were landing, refueling, and taking off again, while the raid was progressing.

The next morning we were loaded into a train which took us into Hanover, where we changed trains for Frankfurt. At the camp in Frankfurt I was placed in a tiny cell only slightly bigger than the sleeping bunk, no windows for ventilation. Across the end of the cell there were two large pipes which were used for heating and these heating pipes the guard regularly turned on absolutely roasting me over a period of eleven days. Ever since I have not been able to take heat as medical diagnosis has been that this heat torture had ruined my thermo regulatory centre of the brain".

From "Tasmanian's At War" author, Brian Winspear.

Being a Tasmanian by birth, and upbringing, the cover note of Brian`s book caught my eye, resulting in the following account.

"The Lancaster had been badly hit – two engines were on fire – the perspex over the pilot was shattered – the aircraft was in an uncontollable spin. The pilot ordered the crew to bale out. He fought in vain to control the aircraft. The engineer couldn`t open the jammed escape hatch. The altimeter was gyrating dangerously – there was little height left. The pilot thought "I am not going to get out of this". He looked up and saw the broken perspex. "That`s my only chance". He stood on his seat and forced his way through the jagged hole. It ripped his pants and caught his leg – he released his chute – it yanked him clear. Seconds later he was flat on his back in the snow, his burning aircraft 50 yards away. The Tasmanian born CO of 460 squadron had just made it. He was back behind his desk in three days.

Keith Parsons

Keith ParsonsKeith Parsons is one of the few Air Commodores in the RAAF and RAF to be a member of the Caterpillar Club. To be a `Caterpillar` you must have baled out of a crashing aircraft by parachute. (The connection between caterpillars and parachutes was because the `chutes were made of silk).

Keith was born in Scottsdale, Tasmania, in 1914, and joined the RAAF as a pilot after studying architecture for three years. As a Flt Lieut he became very good at supervising the erection of pre–fabricated hangars at various locations around Australia. Then when war broke out, he commanded No 1 Air Training Squadron, in 1941–2, 7 Squadron in 1942–3, 5 EFTS in 1944, and 460 Squadron at Binbrook from late 1944. GROUP CAPTAIN, KEITH PARSONS, Commanding Officer, 460 squadron, Binbrook then replaced Group Captain Hughie Edwards as station commander. As Group Captain in command of Binbrook station he was not supposed to fly on ops, but he did so quite often.

He described one disastrous Lancaster flight in an interview with Peter Scully for the Australian War Memorial;–

It was a case of the devil looking after his own. An order had come out from Bomber Command that pilots had to wear seat type `chutes. We were using lap–type, and they found that some people were having trouble getting out of the aircraft because the engineer had to find the `chute for the pilot, hand it to him and then the pilot had to unstrap and buckle it on and all the rest of it. So the pilot interfered with the complete evacuation of the aircraft. I'd put myself down for this trip, and I had one rule over there; I never selected a trip. There was so much comment that various COs went on the easy trips and dodged the tricky ones. So I said that I would get approval to go on the third trip from the day that I asked, so that it would be in the luck of the draw as to which trip it was. You were pretty busy by the time you organised to go on the trip yourself and organised all the briefing and had done all the rest of the jobs that a station commander had to do.

I'd arranged for the briefing and I went to my locker and saw that I had a lap–type `chute. I thought, "Oh bugger it; it's comfortable and why worry." And then I thought, "No you're the CO and if you go out with a lap–type 'chute the blokes will say one rule for the rich and one for the poor sort of thing," So I rang up the parachute section and said that I needed a seat–type 'chute and asked for one to be sent around for me. The sergeant came round to the headquarters with this parachute and sat me in a chair and buckled it up, and everything was sweet. I didn't know that six hours later I'd be hanging onto it.

Now I had a new crew with me – I was navigator trained as well – I always checked the courses and made the pilot–nav check all the time. We were still five minutes from a turning point, you always zig–zagged over Germany. You headed that way and hoped that would alert the people over that way, and then you turned this way and tried to confuse the German defences. We were still about five minutes from this turning point, Flying at about 19,000 feet in wispy cirrus cloud. No nav lights on or anything like that; you always flew in complete darkness. Suddenly, this other Lancaster appeared out of the murk, and he was heading at 45 degrees straight for us and was only about fifty yards away. I still had 'George' (the auto–pilot) in as a matter of fact, and I always took it out before I got to the turning point because I knew things could get hectic, but I still thought I had five minutes to go. So I pulled 'George' out and shoved the stick hard forward, and this bloke wiped right across the top of us, smashing the canopy over the top and collecting my two port engines – actually the engines chewed off his rear gunner and the turret. So we pulled up and almost did a roll, and I tried to level the bloody thing out, but she wasn't behaving very well at all and we went into a very tight spin.

I called the crew to "Bale out, Bale out!" In a Lancaster you have a bomb aimer down ion the nose, and the escape hatch is in the bottom of the bomb aimer's compartment. The engineer goes next, then the navigator, the the wireless operator, and then the pilot follows. The two gunners go out the back. We were spinning down, and they'd all moved forward, and the navigator was standing next to me, but there was no movement forward at all. We used to practise abandoning aircraft, and the whole crew could get out in about forty seconds under normal circumstances, But when the aircraft was spinning everybody would have been very heavy, and they must have had trouble opening the door , I think.

When we past 7,000 feet, I realised that I wasn't going to get out because there wouldn't be time. Then I realised the canopy had been shattered on the top and so I said, "Bugger it, I'll try going out over the top." So I managed to get my head and shoulders through and then my `chute got caught. I broke great chunks of the perspex with my hands and dragged the 'chute through. The spin was so tight that I actually stood on top of the fuselage, quite comfortably, and then I gave one hell of a push off and pulled the rip cord. Then there was a bang as the 'chute opened, and id bruised the inside of my legs as it hit so hard, and the next minute I went bang into the bloody snow.

The aircraft landed only about 50 or 100 yards away and burst into flames straight away. So I gathered my 'chute and ran like hell and sat behind a haystack and got my breath. I looked around and couldn't see anybody, and I got up and went a bit further. I wasn't sure exactly where I was on our side of the line or the German side. I was lying in the snow and thinking how cold it was and I put my hand down and felt I had a bare bottom. I'd torn the seat out of my pants getting out of the plane. I got a bit further away from the aircraft because I realised that although it was burning it had a 4,000lb 'cookie' on board. The bomb load was a 4,000lb. cookie, four 500lb. and eight 500lb incendiaries. The incendiaries were burning nicely and I thought the cookie would go off at any tick of the clock. I got into a ditch then and I saw the lights of a truck coming and I thought "What are they?" They pulled up alongside the fence and got out and I could see they were armed and I thought "Now this will be interesting so I stayed low. Then I heard a Cockney swearing, and he let out a string of invective, which was music to me, as no one could have faked that. They picked me up and I made myself known and they covered me for a while until I proved I was an Australian. Then I went to a police station and they filled me up with brandy. This was about one o'clock in the morning. The CO of the regiment came over and said they'd searched the whole area and had found two crewmen but that was all. One was a bomb aimer who had eventually got out, and they'd picked up another man and told me his name. "He wasn't in my crew," I said. and I thought that I'd had a stowaway. People did stow away from time to time when a gunner would ask them to come along for the ride and see what it was like. They'd stow away in the back and sometimes the skipper didn't even know about it. I finally worked out it must have been the rear gunner of the other aircraft.

The CO took me back to his camp and bedded me down and I finished off a bottle of brandy before I went to bed, and in the morning we went back and looked around the site. We could see the five bodies that had been burnt in the remains. The cookie didn't explode but it had burnt out, which is apparently what happens if the heat is intense enough. The CO then drove me back to Amiens and I was put up in the officers, club there. The doctor from a New Zealand squadron had a look at me and assured me that there were no broken bones.

I asked the CO of the squadron if he could get his blokes to fold my 'chute. He called his sergeant in and he took the 'chute away, coming back a quarter of an hour later and saying, "You didn't bale out with this 'chute." I said "Oh yes I did. I haven't lost sight of it and I have an attachment to it." He said, "No, it's ripped right from the bottom up to the apex. It wouldn't have stayed inflated." "Well it did," and I told him what had happened. "Boy you're lucky sir. That's what happened; it would have opened initially but as soon as it filled with air it would have streamed straight away. So you must have hit the ground just before it started to stream. You wouldn't have been more than 100feet up when it opened." So being responsible and honest and changingmy 'chute had saved my life – I wouldn't have got out with a lap–type. So everything fell my way.

The old Doc came in to see me the following afternoon and said. "We've got a party on, do you feel like coming along?" "Yes, if I can get a batman to sew mr pants up". By that afternoon, I felt really terrible. The shock had set in, and I rang up the Doc at the New Zealand squadron and told him, I couldn't go that evening as I felt so awful. He came and had a look at me and said, "The best thing you can do is to go out tonight. If you stay in bed the only thing you'll do is shake all night." So I went along to the party and went up to the bar. I hadn't had any dinner. He said, "What do you drink?" "Whisky." So I had a couple of whiskies and then he got me onto some cheap champagne. So we stayed at the bar and I was drinking whisky with chanpagne chasers. I started to feel good and there was a pretty girl sitting nearby and I observed she was a lovely girl. The Doc said, "Oh I know her." I asked him to introduce her, so he went over and had a few words with her and brought her over. She said, "The doc said you'd like to have a dance with me." I said, "Yes." The bar was up high and there wre two steps down to the dance floor and I didn't make it. I tripped on the step and fell flat on my face. The Doc must have warned the girl, because he was there straight away and he said. "I think you might sleep now. I'll take you back to the mess and you can go to bed." I passed out cold.

I suppose that for about three months afterwards I used to have nightmares. That struggle to get out. I had a vivid picture of the 'chute being caught and realising that I was running out of time fast and would be severed in the middle when the aircraft hit the ground.

I loved my return to the station. They sent an aircraft down to Northholt in London to pick me up. It was the replacement aircraft for the one I'd lost with the same letter, P for Peter. So teh crew that flew it down asked me if I'd like to fly it back and of course I said yes. So I flew it back and I came into Binbrook and called up landing instructions, "P for Peter, landing instructions." And the Waffy in the tower came back like a flash, "P for Peter land on runway 22 - sir you're a little bit late coming back aren't you." Those WAAF girls knew every voice of the squadron pilots.

A little later, a fellow going on his 30th and last trip was late coming back, after all the oters had landed. I'd go down to briefing, but they would notify everybod that we had a missing aircraft, and they would do a check of all other stations to see if they'd landed on another aerodrome if they had engine trouble or something. I'd just got as far as the door when over the loud speaker came. "Guess who?" The Waffy didn't bat and eyelid, "M Mike from Leary, land so and so," I asked her, "How did you know it was M Mike?" "I know every voice," she told me, "they don't have to tell me who's calling up."

Keith survived the war and stayed in the RAAF to become Officer Commanding RAAF, Butterworth, as an Air Commodore in 1958. He was one of the RAAF's most highly decorated pilots, with the CBE, DSO, DFC, AFC, and is now living in retirement at Rostrevor in South Australia.

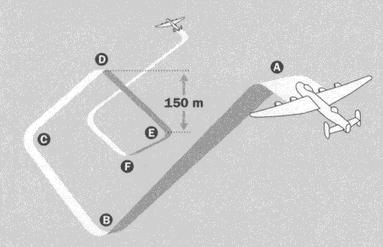

Binbrook Lancaster J2 in 1945 fitted with paddlepop propellors on American Rolls Royce engines. A rare BV11 interim development.

Binbrook Lancaster J2 in 1945 fitted with paddlepop propellors on American Rolls Royce engines. A rare BV11 interim development. Lancaster cockpit showing the controls and instruments for the 4 Rolls Royce Merlin motors.

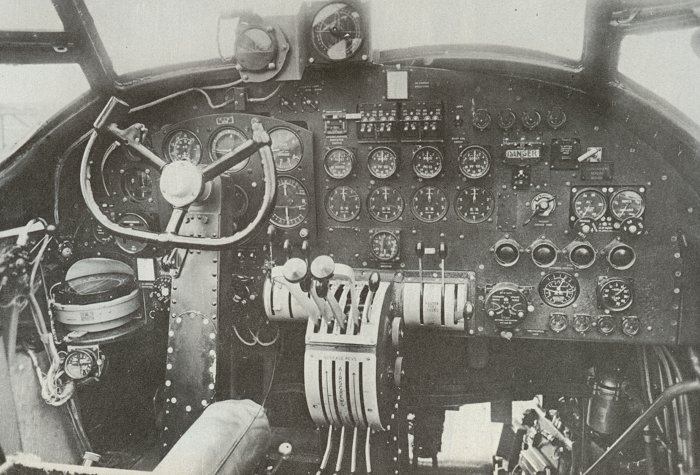

Lancaster cockpit showing the controls and instruments for the 4 Rolls Royce Merlin motors. The bomb aimer's control board.

The bomb aimer's control board. The main spar, a real stumbling block in the middle of the aircraft.

The main spar, a real stumbling block in the middle of the aircraft. Queued up ready for the green light on takeoff.

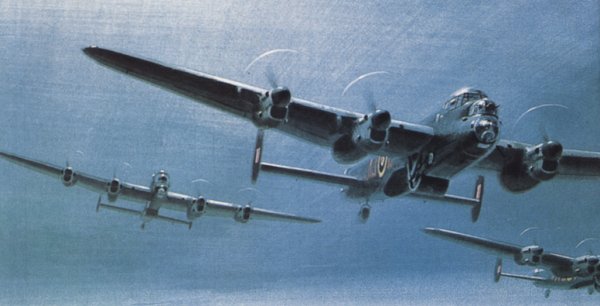

Queued up ready for the green light on takeoff. Climbing for height at the rendezvous point before setting course for Germany.

Climbing for height at the rendezvous point before setting course for Germany. Climbing for height in the bomber stream.

Climbing for height in the bomber stream. Banking onto a new course.

Banking onto a new course. The bomber stream heading for the target.

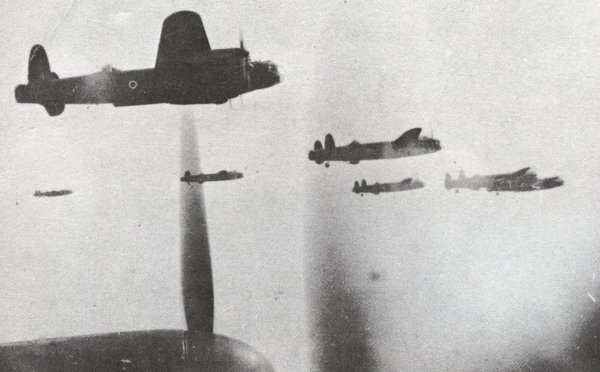

The bomber stream heading for the target. With such a concentration of heavy bombers as it got darker it was no wonder that collisions were part of the dangers to crews.

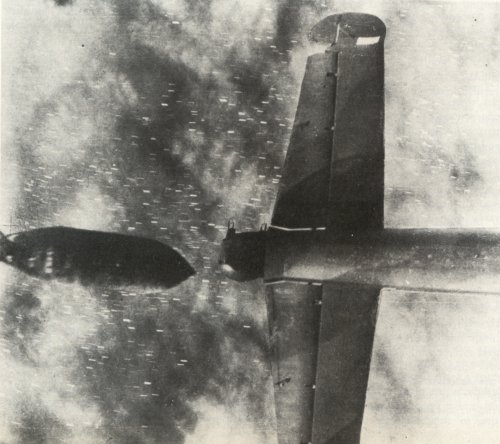

With such a concentration of heavy bombers as it got darker it was no wonder that collisions were part of the dangers to crews. What a fright for the rear gunner. A falling 500lb bomb almost ready to part his hair.

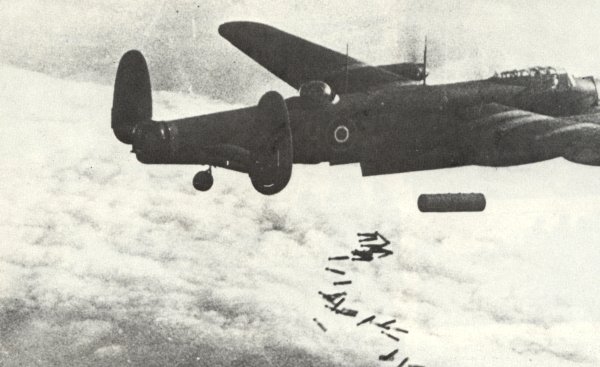

What a fright for the rear gunner. A falling 500lb bomb almost ready to part his hair. Lancaster unloads its "Cookie" and incendiaries over the target.

Lancaster unloads its "Cookie" and incendiaries over the target. A direct hit.

A direct hit. Turning point on route, banking onto a new course.

Turning point on route, banking onto a new course. Incident over Hannover, 8 Oct 43 by Eric Day: One Lancaster is on fire and this was quite a common occurrence after the planes had been hit by ack–ack or been set on fire by the German fighter planes.

Incident over Hannover, 8 Oct 43 by Eric Day: One Lancaster is on fire and this was quite a common occurrence after the planes had been hit by ack–ack or been set on fire by the German fighter planes. Always danger from bombs falling from planes above.

Always danger from bombs falling from planes above. Not everyone could afford nor wish the luxury of a bath on the way home.

Not everyone could afford nor wish the luxury of a bath on the way home. Group Captain Edwards talks with Warrant Officer Geoff Walker, Pilot Officer Jack Reinhardt, and Flight Sergeant Alan Reid on their return from a raid.

Group Captain Edwards talks with Warrant Officer Geoff Walker, Pilot Officer Jack Reinhardt, and Flight Sergeant Alan Reid on their return from a raid.